International cooperation for universal literacy – marking International Literacy Day 2024

One of the early priorities of the United Nations was its campaign for universal literacy. Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1965 the campaign recognised illiteracy as a pressing global issue. The UN General Assembly global plan for universal literacy was viewed as part of the international community’s commitment to create the conditions for “dialogue among cultures, peoples, and civilizations”.

Literacy is still regarded as a critical foundation for acquiring broader knowledge, skills and values and as a means of fostering a culture of lasting peace based on respect for equality, non-discrimination and the rule of law. Literacy empowers individuals, improves livelihoods, enables greater participation in society and the labour market, benefits child and family health and nutrition, and reduces poverty.

However, despite all these benefits, almost sixty years after the world first committed to ensure everyone should be able to read and write, progress has stalled and there is a real and pressing risk that the number of illiterate adults will increase.

Today, 765 million adults, two thirds of whom are women, still lack basic literacy skills. This figure hasn’t changed in decades because adult literacy programmes are a low priority for most governments.

In 2016 the Global Alliance for Literacy was launched with the aim of boosting policy development and financial investment in youth and adult literacy programmes to advance the UN’s original aim of literacy for all. UNESCO’s Institute for Lifelong Learning supports the Alliance which consists of 30 countries with high rates of adult illiteracy.

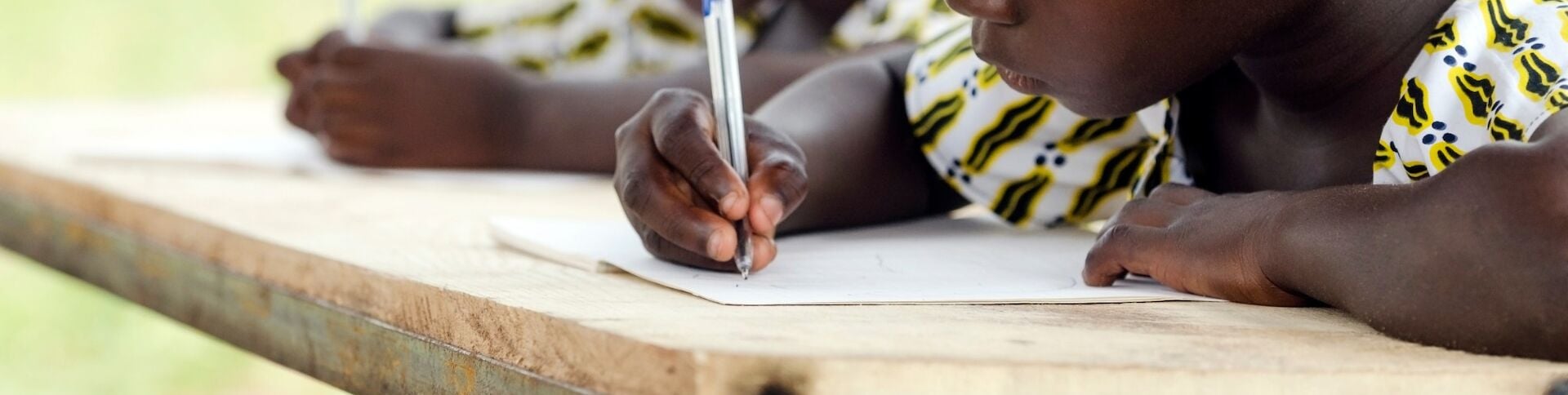

Unfortunately, as educational progress slows, we now face a serious risk of adding to the population of adults without basic literacy skills. Almost 25 years after we promised to ensure every child would complete primary school there are 250 million out of school children around the world. Without access to school, they won’t learn how to read.

However, we also know that access to education alone does not guarantee learning. Only one in five children who reach the end of primary school in Africa will achieve a minimum proficiency level in reading. In low-and middle-income countries across the world, 70% of ten year olds, either because they haven’t been to school or because the quality of education they receive in school is inadequate, can’t read and understand a simple text.

Creating a global coalition

UNESCO is working with UNICEF, the World Bank, and the United Kingdom and the United States in a coalition to turn this crisis in foundational learning around. This coalition is advancing on several fronts. Firstly, it allows us to speak with one voice on the vital importance of foundational skills. This is important because officials in partner governments consistently overestimate the learning levels of their students and underestimate the significance of persistently low levels of learning.

As the former President of Nigeria Olusegun Obasanjo wrote, “my fellow leaders have not yet seemed to fully grasp the urgency and severity of the situation.”

The coalition’s flagship report ‘The State of Global Learning Poverty’ sets out both the extent and significance of the crisis in foundational skills. The coalition is advancing on other fronts – closing the learning data gap, building evidence on how to promote foundational learning for all children, and providing coordinated financial and technical support to countries that show real commitment to reducing learning poverty.

In 1967 when the UN proclaimed September 8 International Literacy Day its aim was to remind policymakers, practitioners, and the public of the critical importance of literacy. 57 years later that aim is clearly as important and as urgent as ever.

International Literacy Day underscores the importance of literacy and invites us to recommit to the unfinished business of ensuring everyone can read and write.