One of the most striking and visible consequences of the steadily rising temperatures - with profound implications for communities across the globe - is the rapid melting of glaciers in mountainous regions. The most severely affected areas include the Greater Himalayan region, the Andes, the European Alps, and East Africa, where glaciers are retreating at accelerating rates. According to the United Nations, around two billion people live in villages, towns, and cities either within these mountain tracts or further downstream on extensive lowland plains, and they rely—directly or indirectly—on freshwater from glaciers.[1] This water is vital not only for domestic consumption, crops, livestock, industry, and electric power generation, but also for sustaining fragile regional ecosystems and biodiversity.

Glaciers shrink, water is scarce, lives are at risk

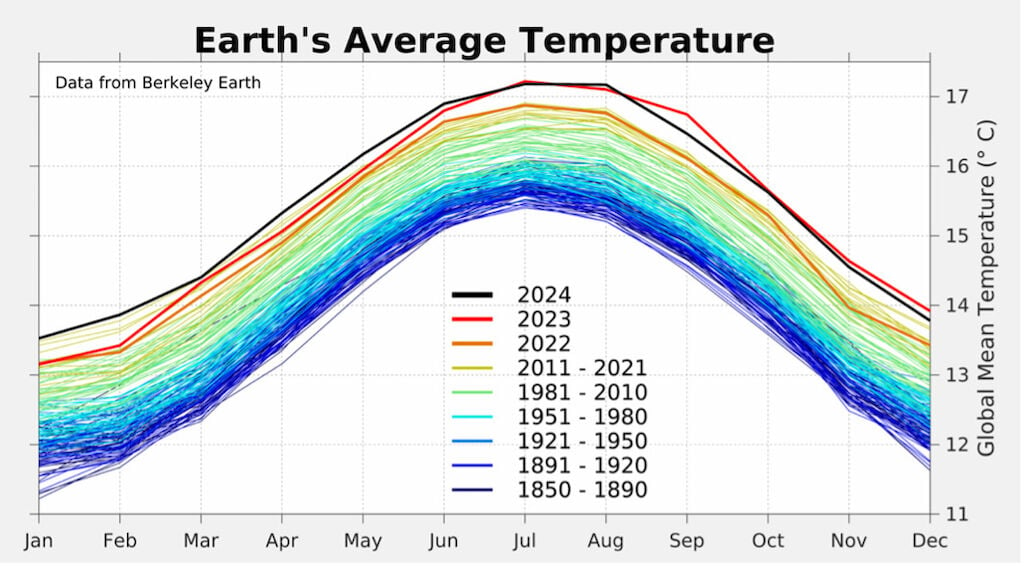

Our planet is in trouble; it is warming at a dramatic rate. The likelihood of restraining global temperatures from rising above 1.5°C over pre-industrial levels, an ambition set out in the UN Paris Agreement, seems remote. There is an inexorable increase across most of the globe of 0.20°C per decade; the warmest years on record were all in the last ten years Figure 1).

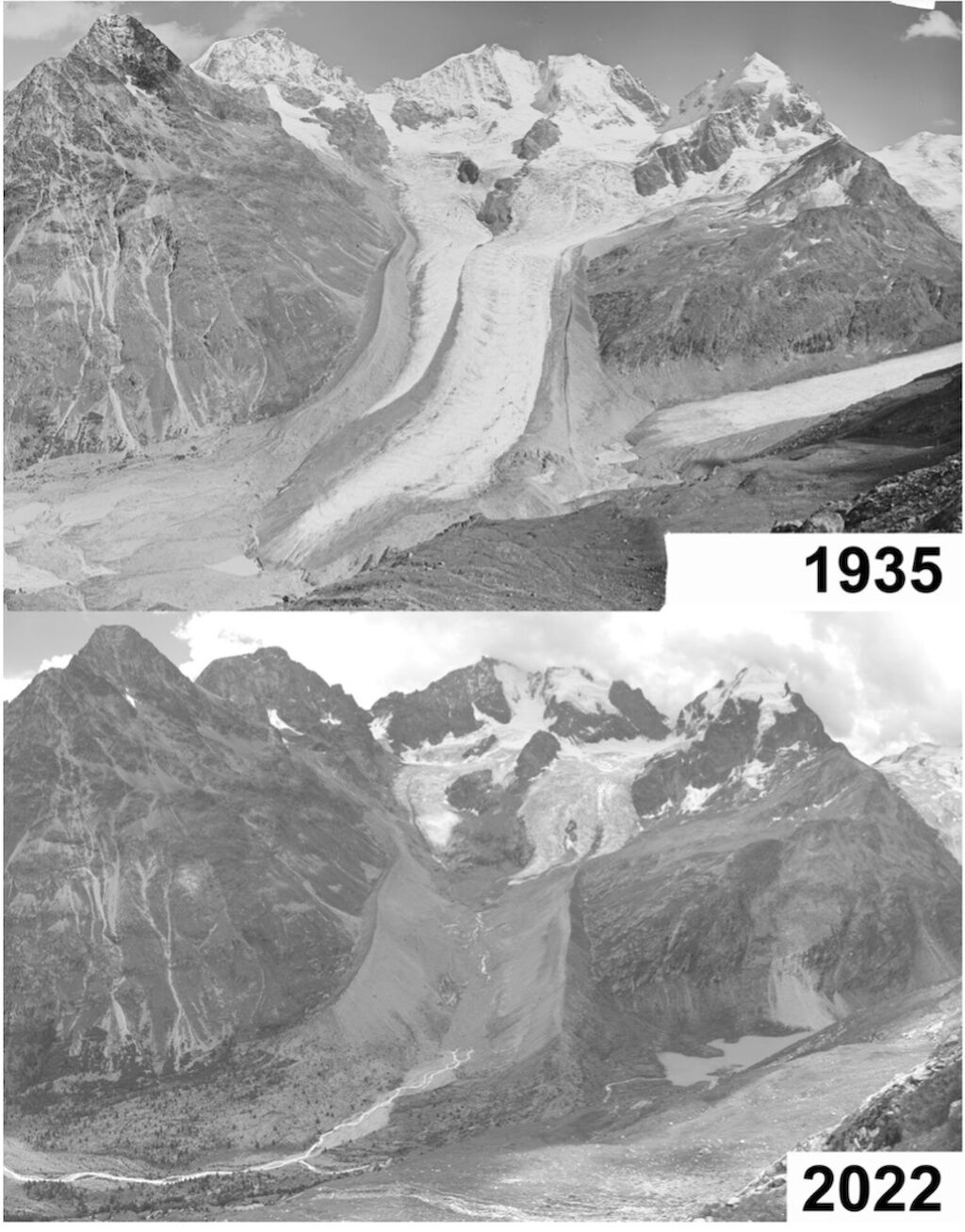

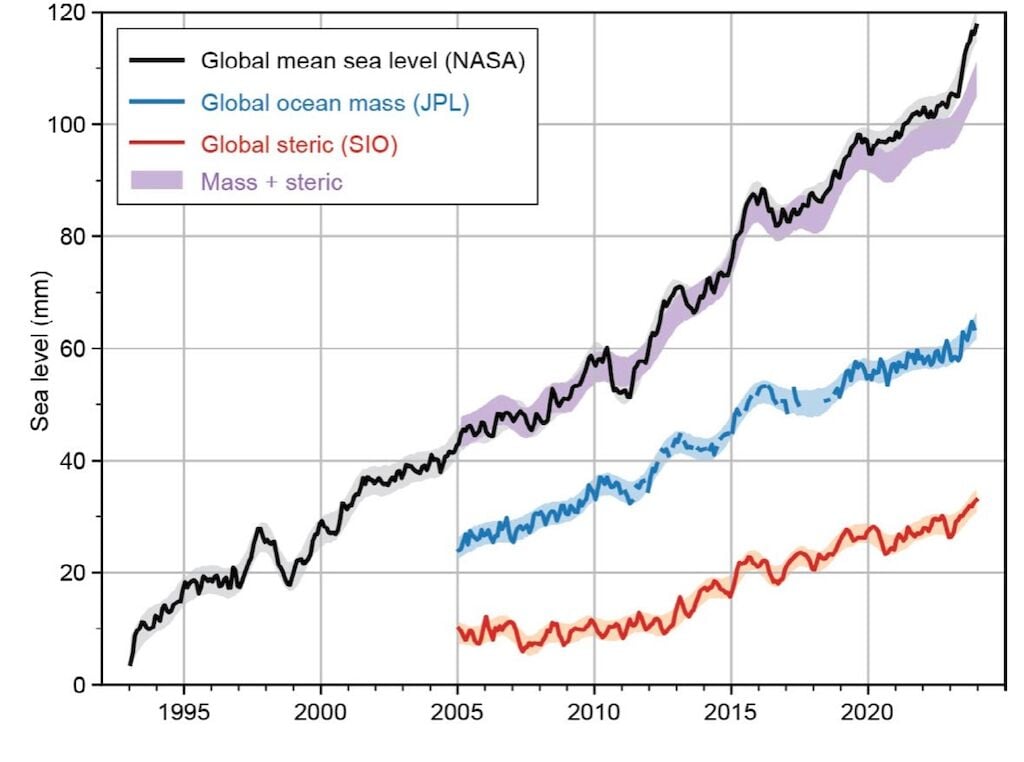

The changes taking place are dramatic. In the Andes, 25 per cent of the ice has disappeared since the Little Ice Age (early 16th to mid-19th century), while in the Hindu Kush, half of the remaining glaciers are projected to vanish under 2°C of warming. Switzerland alone lost 10 per cent of its glacier volume between 2022 and 2023 (Figure 2). According to the IPCC, such levels of warming could be reached as early as the 2040s under high-emissions scenarios, and by the 2060s if current emission trends continue. Over the past two decades, glaciers worldwide have been shedding approximately 273±16 gigatonnes (Gt) of ice annually [2]. The further consequence of this loss is its growing contribution to sea level rise: melting glaciers and ice sheets are expected to raise global sea levels by 25 to 50 centimetres over the next 75 years, depending on whether emissions follow low or high pathways [3]. In all likelihood ice loss will accelerate.

Glaciers waste away and flooding looms

The consequence of rapid glacier melting is being felt with increasing concern by almost all mountain communities. Chhireng Tamang has lived the whole of her 75 years in Langtang National Park, in northeastern Nepal. This is a place of high-altitude with glaciers, snowpacks and exhibiting considerable biodiversity. Chhireng recalls a period when the mountains received regular and heavy snowfall, and the glaciers were “white and big.” This meant it was easy to farm yaks, an animal upon which many rural communities still depend for wool, milk and meat. Rising temperatures have rapidly reduced the amount of water and fresh grass available for the livestock. From a herd of forty yaks, Chhireng Tamang now has just nine. “There is not enough grass to feed them anymore. All the farmers face the same problem,” she says [4].

An added concern in high mountain communities is the growing danger posed by the collapse of glacial lakes giving rise to devastating floods. Along the sides or at the fronts of the glaciers—often dammed by unstable morainic debris—these lakes form and fill rapidly as the ice melts due to rising temperatures. Fed by increased volumes of meltwater, more frequent high intensity atmospheric storms and massive landslides of ice and rock, these natural and unconsolidated “dams” burst releasing immense quantities of water (termed Glacial Lake Outburst Floods —GLOFs) that surge down the high valleys to the populated foothills.

In the Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa regions of the Himalaya, for example, there are over 3000 ice-dammed lakes of which over 30 have been identified as vulnerable and at risk of bursting, endangering over 7 million people [5]. Over the last 70 years in the Cordillera Blanca of Peru, several thousands of people have been killed by GLOFs. [6] Since 1833 over 70 per cent of the 700 GLOF outbreaks in the Karakoram have happened in the past 50 years.

Thawing Permafrost

Associated more readily with vast tracts of Arctic terrain, permafrost is nevertheless a distinctive feature in high mountain regions, determined by elevation, topography, aspect, snow and vegetation cover. It is ground that is frozen from at least one winter season to the next and occurs in the Himalaya at elevations above 4000-5000m. The depth of permafrost extends to many hundreds of metres. Knowledge of the extent and depth of permafrost in the greater Himalaya and Hindu-Kush regions is poor, however; recent estimates place this at about 1M sq.kmexcluding Tibet [7].

There is clear evidence of widespread thawing. For the western Himalaya one study has suggested a reduction in permafrost cover of 8,340 sq.km between 2002/04 and 2018/20. The consequences are varied from damage to highways and buildings to impacts on hydrological processes, biodiversity ecosystem functioning.

Rising temperatures are also destabilising frozen mountain slopes and weakening ice-bonded sediments resulting in severe and more frequent rockfalls and ice-debris avalanches. Often these have plunged into adjacent lakes - a further cause of severe flood events – GLOFs - referred to earlier. In the Peruvian Andes at Salkantay a massive rock avalanche (some 1-1.5 M m3) in 2020 crashed into a lake triggering a major flood to villages down valley with loss of lives [8]. The massive rock and glacier collapse at Blatten in Lötschental in Switzerland in May 2025 is a further indicator of the instability caused by rising temperatures.

Rising Sea Levels - the polar contribution

Away from mountain glaciers, the vast ice sheets of the sparsely populated polar regions might seem of lesser concern. Yet they pose a growing and urgent global threat, increasing year by year. In the Arctic, temperatures are rising more than three times faster than the global average, accelerating the pace of ice loss. Ice caps and the Greenland Ice Sheet are melting rapidly discharging vast volumes of freshwater into the world’s oceans. Greenland alone is now losing around 270 gigatonnes of ice per year — a fivefold increase compared to just two decades ago.

In Antarctica, glaciers in the Antarctic Peninsula and the ice sheet in West Antarctica are the fastest warming regions of the continent. In the second half of the 20th century, temperatures rose by 3.2°C, contributing to the collapse of several smaller ice shelves. Overall, the continent is now warming at a rate nearly twice that of the rest of the world. The ice sheet, consequently, is losing mass at an accelerating rate. Between 1979 and 2022, the loss averaged 4,790 ± 987 gigatonnes per year. West Antarctica contributed approximately 80 percent, while 18 percent came from the Antarctic Peninsula.

The melting of the two great ice sheets combined with the contribution from mountain glaciers around the world as described above account for about 45 percent of the rise in mean global sea level [10]. (Figure 3).

Communities living at or close to sea level are increasingly threatened by ocean flooding, storm surges, and coastal erosion. António Guterres, UN Secretary-General, recently warned, “Mega-cities on every continent will face serious impacts…the danger is especially acute for nearly 900 million people who live in coastal zones at low elevations.” [11]. These vulnerable populations are found on every inhabited continent and across hundreds of low-lying islands scattered throughout the world’s oceans. Both developed nations and least developed countries are at risk. By 2050, the additional rise in global sea level is estimated to be approximately 17.0 cm [12].

In Florida, some observers argue that the coastal fringe is already “drowning.” An estimated 100,000 to 145,000 properties near the shoreline face significant flood risk, and by mid-century, iconic landmarks like art deco hotels and the famous Ocean Drive are projected to be underwater. Meanwhile, saltwater intrusion is contaminating fresh water from the Biscayne Aquifer, raising concerns that local water supplies may soon fall short of demand.[13].

Meanwhile in the Pacific whole nations are threatened. Five small islands in the Solomons have disappeared already and many others are in the process of being overwhelmed (Figure 4). By mid-century continued habitation in places like Tuvalu will become perilous. One resident, Teuleala, a retired civil servant, reports coastal erosion is having damaging impacts. On one of the islands, waves are over-topping it during storms, and flooding homes. Houses have to be built on stilts so families can escape flooding during cyclones. She says, “I believe in these islands, but we’ve been told we have another thirty years to go.” [14]

An uncertain future

The International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation (IYGP) is dedicated to raising awareness of the urgent challenges posed by accelerating ice loss, enhancing scientific understanding, and shaping policy responses across all levels of governance. Yet, despite mounting evidence and increasingly visible climate impacts, most governments have failed to respond with the necessary scale or urgency. Short-term political and economic priorities continue to take precedence over long-term environmental resilience. COP-30 has much to consider.

In the absence of bold and coordinated leadership, the loss of glacial ice - both in polar regions and mountain ranges - is expected to accelerate, with far-reaching global consequences. Unless the international community fully acknowledges the severity of the threat and takes ambitious action, sea levels will continue to rise, and much of the world's glacier mass will vanish. For affected populations facing flooding, water scarcity and food insecurity, the only remaining path may be phased adaptation, and in some cases, managed retreat from increasingly uninhabitable areas. Time is not on their side; their courage and fortitude undeniable but their resilience is limited.

Footnotes

[1] UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme, 2025, Mountains and Glacier: water towers, 174pp; https://doi.org/10.54679/LHPJ5153

[2] The GlaMBIE Team, 2025 Community estimate of global glacier mass changes from 2000 to 2023, Nature 639, 382-388. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08545-z#Abs1

[3] As Footnote (2)

[4] Johan Augustin, 2021 As its glaciers melt Nepal is forced into an adaptation not of its choosing, MongaBay 27 December

[5] Melting glaciers, growing lakes and the threat of outburst floods, UNDP CLIMATE 26 August 2022

[6] Emmer, A. et al. 70 years of lake evolution and glacial lake outburst floods in the Cordillera Blanca (Peru) and implications for the future. Geomorphology 365, (2020).

[7] Gruber et al 2017 Review article: Inferring permafrost and permafrost thaw in the mountains of the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, The Cryosphere, 11, 81–99, 2017 www.the-cryosphere.net/11/81/2017/ doi:10.5194/tc-11-81-2017

[8] Petley, D, 2020, More information about the Salkantay landslide and mudflow AGU The landslide blog, 28 February, 2020

[9] Casado, M et al. 2023 The quandary of detecting the signature of climate change in Antarctica. Nature Climate Change 13, 1082-1088

[10] Greenland 22%, Antarctica 7%, 15% mountain glaciers. The remainder from land waters and, importantly, thermal expansion of the upper level of the world’s oceans (35%).

[11] UN Secretary General, UN Security Council Debate on “Sea level rise: Implications for International Peace and Security”, February 2023

[12] Hamlington, B D et al 2024 The rate of global sea level rise doubled during the past three decades, Communications earth & environment. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01761-5

[13] Luscombe, R. “Will Florida be lost forever to the climate crisis?” The Guardian, 21 April 2020

[14] Aili Channer, 2025 Island Stories: Perspectives on Climate Change from the Pacific, Oxford Climate Society (Insights 11 April)