1st World Day for Glaciers and World Water Day Event: 2025 International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation

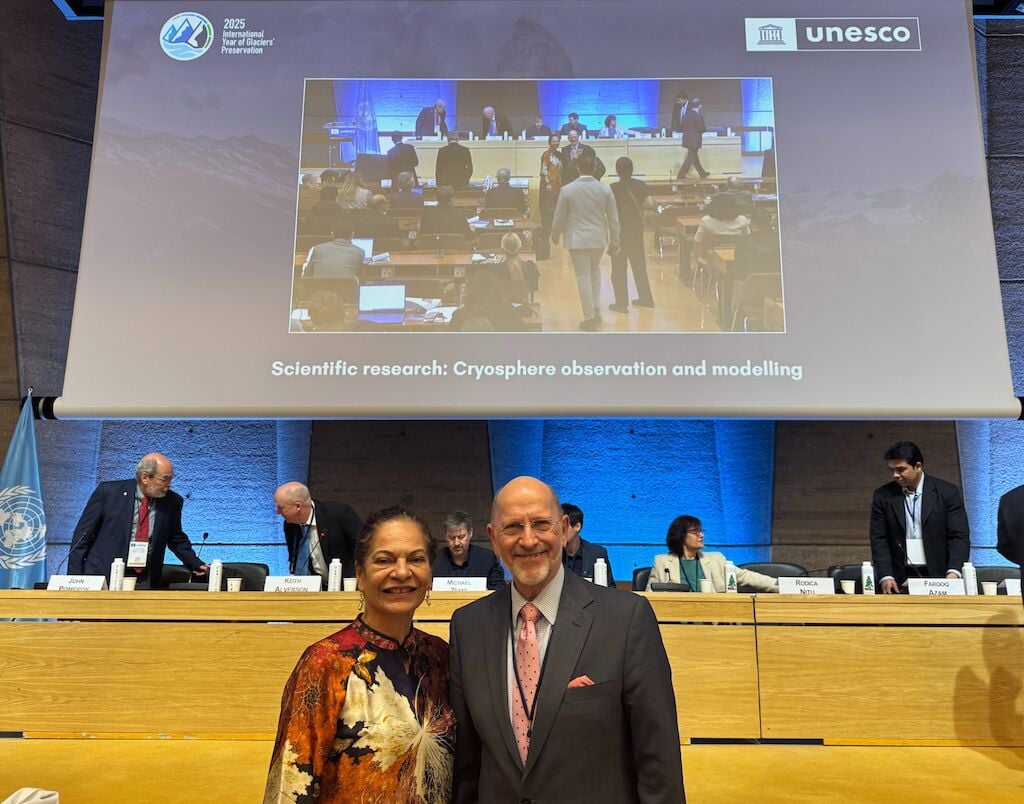

On the 20 & 21 March 2025, David J Drewry, UKNC Non-Executive Director for Natural Sciences, attended the celebrations to mark the 1st World Day for Glaciers and World Water Day in UNESCO, as part of the International Year of Glaciers' Preservation 2025.

The blog below outlines David's reflections of those two days and how both the preservation of glaciers', and adaptation strategies to cope with their melting, are vital to the survival of millions of people across the globe in the coming decade.

Around the globe citizens and politicians are beginning to realise the important role that ice plays in the life support systems of our Planet. Two Billion people rely in some way on the water that the regular melting of glaciers provides for drinking and sanitation, for agriculture, industry, power production as well as supporting the natural environment.

But the glaciers are retreating and diminishing due to our warming climate and at an accelerating rate. This is why the United Nations passed a resolution for their future preservation and asked UNESCO and the World Meteorological organisation (WMO) to take this matter forward.

Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences

2025-2034 has been declared the Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences and to the commence of the decade of action, 2025 is the International Year of Glaciers' Preservation (IYGP).

The two day event in Paris was the formal start of the International Year and established the 21 March as the annual 'World Day for Glaciers'.

The first day of the event saw leading experts from around the world presenting scientific insights into how glaciers are reacting to climate change in the high mountain regions particularly the Andes and the greater Himalaya, but also the Alps and Rockies.

In these places communities are highly dependent on glacial water especially in the dry season when rainfall is low or negligible. Glaciers at these times continue to supply water to communities down-valley and contributing to the water flowing into the plains, to towns, cities and extensive farming area in the lowlands. We heard much about the loss of ice, monitoring of glacier decline, associated impacts such as glacial outburst floods from weakened and overflowing lakes, threatened permafrost, and changing patterns of snowfall.

The need for future adaptation strategies

Although the Decade is about the cryosphere little was said about the great ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland which are also showing signs of reduction due to atmosphere and ocean warming with disastrous consequences for global sea level rise. The overall focus was mountain ice.

Much was said about the need for glacier “preservation”. In my interventions, however, I reminded delegates that we have no chance in reducing global temperatures by 2°C or more within the next 100 years which is the only way we will stem glacier melting. As a result, action has to be on how we respond to the new circumstances and focus on adaptation strategies and the opportunities they present.

The future is challenging for those living in the high mountains and the many hundreds of millions of individuals and families who occupy homes and businesses close to sea level whose properties will be threatened by flooding from rising sea levels compounded by storm surges.

The meeting was well attended and, in my UK UNESCO National Commission role as Director for Natural Sciences, I was delighted to support the several scientists from UK universities and institutes who presented valuable insights from their research. This meeting was a valuable commencement to both the activities in 2025 but also for the longer term decade.

More Information On The International Year Of Glaciers' Preservation

The UK National Commission's Contribution

As a contribution to the IYGP the UK National Commission for UNESCO will publish a compilation of articles on these current glacier topics from scientists at UK universities under the title 'GLACIERS AND ICE SHEETS IN A WARMING WORLD: Impacts and Outcomes'. We hope this will be available in the early summer.

About David Drewry

Professor David Drewry is a world leading expert on the environment and study of the polar region. His experience includes Director of both the British Antarctic Survey and the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge University.