Priya Subramanian – October 7, 2022 – 18 min read

Having survived a doctorate study, post-docs step into the world with a feeling of having conquered difficulties, of having transformed from the ingénue who started the PhD program. But the leaky pipeline strikes again, with large attrition rates at the uncertain and nomadic stage of being a post-doc. Here we discuss a few perspectives that might help us weather this journey of being a post-doc.

A venture in self-transformation that starts out as an adventure (the departure), takes a few turns till we face a decisive crisis (the initiation) and emerge victorious (the return) is, in a nutshell, how comparative mythology defines a hero’s journey [1]. Almost all Doctors of Philosophy will be able to self-identify with the above transformative journey during their doctorate. A detailed article on analysing this similarity [2] is motivated by the high attrition rates observed among doctoral students, even ones who have been selected specifically for their potential to succeed!

This blog is similarly motivated at trying to circumvent high attrition rates at the next stage of a career: that of being a post-doc. Note that irrespective of being in academia or braving the ‘real’ world, I mean attrition as inability to continue our self-transformative journey in a fulfilling job that we are happy to wake up to do. It is undoubtedly written from my own skewed perspective of wanting to stay in academia and so focusses on how to get a permanent job at a University, but most of the points are easily translated to non-academic settings. All of the following is based on observations and lessons from my own post-doctoral journey and that of colleagues who’s journeys have intersected mine.

Our doctoral certificate is proof that given patient guidance and time, we are each stubborn enough to finish what we started and are able to communicate it to others. This is equivalent to the end of an apprenticeship in learning a trade and indicates that we are competent enough to work as an employee. Medieval trade guilds used to call such workers, `journeyman’ [3]. Journey(wo)men travelled to gain experience working under different masters in what constitutes `on-the-job training’, slowly evolving beyond the styles and traditions of their apprenticeships, so that they could contribute and advance their field of expertise. Sound familiar, fellow post-docs? Until recent times, the academic equivalent of this was the habilitation, which culminated in a habilitation thesis. Upon successfully defending a habilitation thesis, it was deemed that the holder was ready to profess their area of expertise and to take on their own students. This was the final recognition from peers that one is ready for a full-time academic career. Science requires testing a hypothesis before acceptance and this means that most progressions or promotions in our career feel like we are walking through to an already familiar room. We will only get there if we have already proved that we can handle all aspects of that position 🙂

First and foremost rule for survival I have learnt from my husband is to remember to behave like we are SELF-EMPLOYED. This is because till we get to a permanent position (and even beyond), our focus and time are the only things that we have to offer any employer. Collaborations, affiliations or pedigree with well-recognised names will only shelter us temporarily. Taking responsibility for projects where we are involved and sustaining timely and open communication with collaborators is critical for multiple reasons. Collaborators need to know if you are stuck or having to focus on life in the short-term, and will be understanding and patient if informed well before a looming deadline or pre-agreed date to deliver results. The rest of this blog points out a few key perspectives that are parts of thinking like a self-employed person, which have served me well in my post-doctoral years.

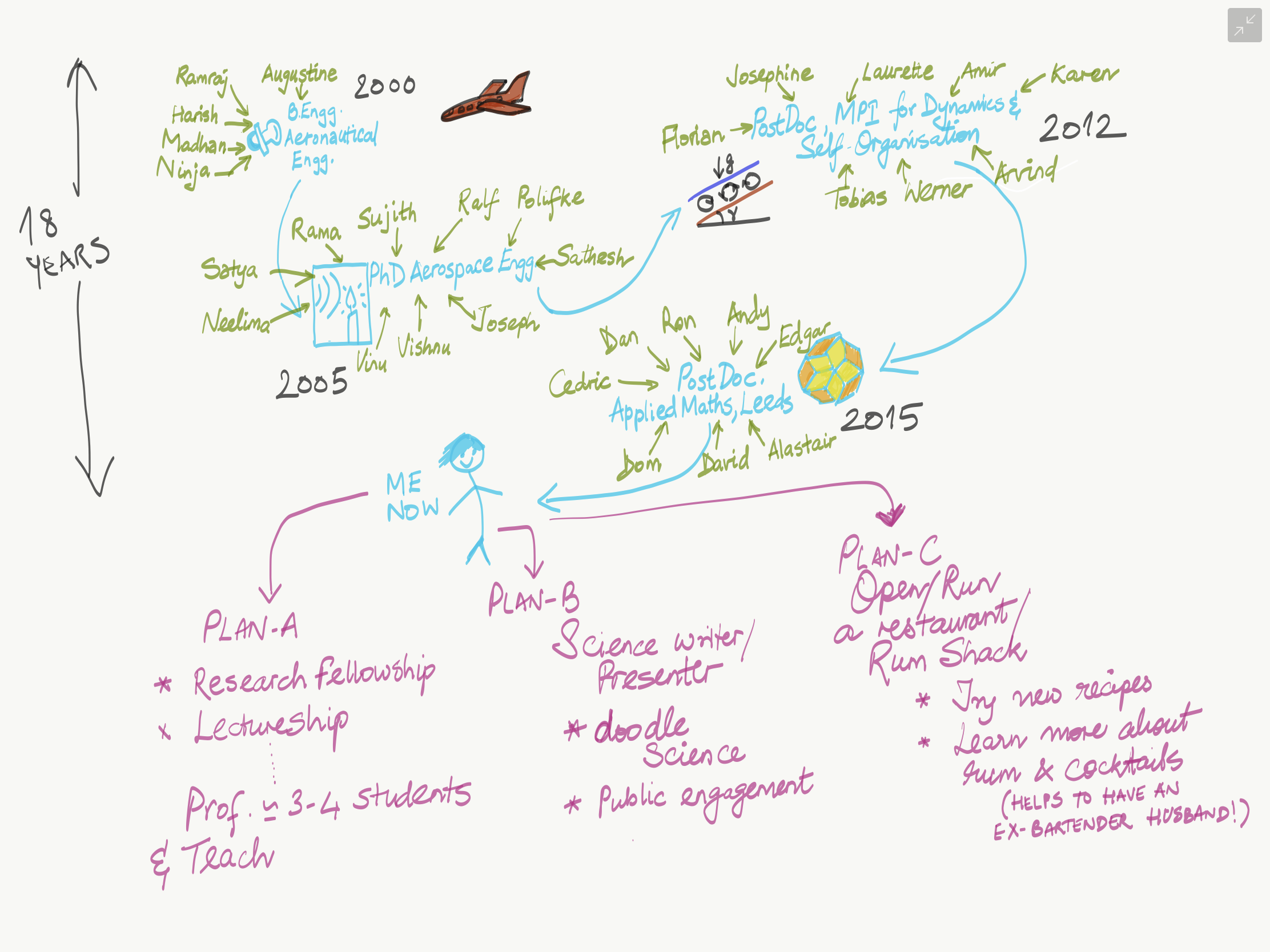

DIVERSIFY. Attending what I thought would be a boring organisational and development workshop titled `Academic next steps’ in 2018 changed how resilient I am. We drew cartoons of our past and were asked to think of 3 alternate futures for ourselves (see Figure 1). Plan A was predictably about what we really dreamt of for our future (I chose to become a professor). Plan B was what we could do using the same skill set that we develop for Plan A, assuming we didn’t succeed with Plan A (I wanted to write scripts for science documentaries and communicate science to the public). Plan C was a career with no connection with Plan A, that would make us happy even if we didn’t want anything more to do with Plan A (as I enjoy cooking for others, my plan was to open a restaurant if I ever wanted to leave academia). We were told that we should start doing something about each of these plans now and not wait for Plan A to fail before we pursue Plans B and C. This was the key thing! I started looking for opportunities to engage with the public for my Plan B and that has introduced me to many academics, and serendipitously increased my chances of fulfilling Plan A! It made me feel like I had options, which is an enormous luxury to have during the uncertain post-doctoral years of revolving applications for the next job.

START BEFORE YOU ARE READY. The road to your Plan A goal from where you are currently, might be paved with multiple qualifying mini-goals. One way to identify such mini-goals is to look at history of people who have gone on to walk this path before. Looking at what happened to them or what they did (in their CVs) can help identify opportunities that you might not otherwise know. Another important way to identify mini-goals is to show your current CV to a mentor, tell them of our ambition in Plan A, and ask them to comment on what the current CV needs to add in the next years. Mentors would not want to push you in directions you might not want to go and so might wait for you to make your intentions clear before offering guidance. So the road to creating a competitive application and CV needs to start well before we feel ready to apply for that job/fellowship/funding and begins with clearly stating our intentions, both to ourselves and others. If listing what you want to do seems difficult, I find that starting with listing what you do not want to do helps.

KNOW THE ODDS. ACT LIKE THEY DO NOT LIMIT YOU. Speaking of applications, it is a very humbling exercise to calculate what the odds are for our success. Current rates for success in a prestigious international research fellowship range anywhere in the single digits, e.g., Royal Society’s URF success rate for 2015 was 8% [4], while it is not uncommon for more than 300 researchers to apply for 6 spots, giving a success rate of 2%. Knowing the odds should help us remember that marginal odds decide any single applicant’s outcome, so that we can shrug off a failure and to move on to the next application. Letting abysmal odds not limit our efforts is the only way to increase the odds of us facing success, whatever attire she may choose to wear!

WITH GREAT FREEDOM COMES GREAT RESPONSIBILITY. Our post-doctoral years are filled with things to do in addition to research and publishing. Most positions come with obligations to teach, mentor, tutor to name a few. This may feel like we are being asked to do more by taking time away from what we love doing most: research. It might even feel like we are wasting our time, when we are not focussing on research. A more palatable view of such a situation is to take this as a training-wheels included taste of life as an academic. Difficulties at this stage to manage expectations can be mitigated with help and advice from mentors and colleagues. Think in extremely large and long scales, to see today’s `chores’ like teaching, applying for funding and academic citizenship activities (grading, admissions, open days, outreach, etc) in a new light. These unpalatable and stressful situations are where we are paying it forward to help our future selves get jobs, but also more crucially helping to collectively sustain the whole framework of the University as a place where everyone gets paid to follow their research interests; the price for the freedom of being self-employed.

FOLLOW UP. BOTH ON PEOPLE AND ON IDEAS. Life is rarely linear. Interesting ideas and people almost always show up when we are in the middle of other work and/or life projects. Trailing ends of conversations with mentors and colleagues are peppered with `Oh, you may want to talk to/try to/read/think about blah-blah-blah’, and hidden behind each one is a possible future collaboration or project or the next big idea! We might not know how to attack such an inopportune fork of an idea at the current moment, but noting down such possible roads to be taken and reviewing them periodically can help us make the most of them. Letting ideas marinate and then following up on them does produce better results! Finally, contrary to popular belief, RESEARCH IS AND SHOULD BE A SOCIAL ENDEAVOUR. It definitely pays to have a diverse network of contacts to learn from and share our expertise with. It is also mentors, colleagues and students that enrich our work life in academia and amongst whom we find some lifelong friends. Kind colleagues, mentors and the above pointers have helped me survive my journeywoman years.

Wish you all the best in your journey(wo)man travels and I am happy to chat/email if you think I can help in any way!

Email: [email protected]

References:

[1] Wikipedia: Hero’s journey, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero%27s_journey

[2] Salter, D. W., An archetypal analysis of doctoral education as a heroic journey, International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 14, pg.525-542, 2019. https://doi.org/10.28945/4408

[3] Wikipedia: Journeyman, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journeyman

[4] Linked from Wikipedia: Royal Society University Research Fellowship, reference number 3, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Society_University_Research_Fellowship#cite_note-pdf-3

Priya Subramanian was one of the five Loreal-UNESCO Women in Science UK winners in 2017, when she was a post-doc at University of Leeds. She then moved to being a Hooke fellow at the Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford between 2019-2021 and is currently a senior lecturer in Mathematics at the University of Auckland. This article is part of her Plan-B and recently she has made some more progress towards her Plan-C by working as an intern at a contemporary Indian restaurant (Cassia) in Auckland once a week.

Share this via…