Sara Jane Potter – January 21, 2021 – 24 min read

Mark Edwards was the first photographer of his generation to specialise in photographing environment and development issues. The defining moment that set him on this track was getting lost in Sahara desert. A Tuareg nomad rescued him and took him back to his people. He rubs two sticks together and lights a fire; they have a cup of tea, and he turns on an old cassette player. Bob Dylan sings A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall. Edwards has the idea to illustrate every line of Dylan’s extraordinary lyric. One of the most widely published photographers in the world; his pictures are in museums and private collections and have been exhibited in galleries in Europe and the US.

I want to speak up for getting lost: lost in the world, lost in the face of problems that seem to have no real and lasting solution, lost in the company of people who always know where they are going.

I’ve found that being lost is a real education, an opportunity to discover something new. When you’re lost, you’re fully alive – open to new ideas – new ways of thinking. Getting lost is the start of an adventure, education at its best is an adventure.

I discovered this when I got lost in the Sahara Desert. It’s the 20th July 1969. A Tuareg nomad rides out of the sands and takes me back to his people. He sits me down and rubs two sticks together to make a fire; we have a cup of tea. Then he turns on an old cassette player and Bob Dylan sings A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.

At the same time, Astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin are taking photographs of the Earth as it appears over the edge of the Moon.

No evidence of human life can be seen at this scale. Dylan’s lyrics provide the close-up; sad forests, dead oceans, broken tongues, guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children. Hard Rain shows how our problems are linked by cause and effect and need to be tackled together. The singer is going to do the job of an artist in threatening times: “I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it.” It will be well-informed speaking: “I’ll know my song well before I start singin’.”

“Hard Rain shows how our problems are linked by cause and effect and need to be tackled together.”

© Mark Edwards

I had the idea to illustrate each line of Dylan’s poetic masterpiece. As I travelled around the world on photographic assignments for magazines, NGO’s and the UN, I added pictures to the song; friends contributed their photographs.

Eventually Dylan saw what we had produced and generously gave me permission to make an exhibition, a book and a film.

The exhibition opened at the Eden Project, a botanic garden dramatically reimagined in an abandoned china clay mine in Cornwall in South West England, in 2006. Both Tim Smit, Eden’s CEO, and I were apprehensive. Many of the photographs are hard hitting, they confound the timid idea that you must not show problems, only solutions. We were reassured when a group of students clustered around the display and wouldn’t return to their bus for the journey home. Later they invited me to give a talk at their school. When I finished, they asked if I’d do it again in the evening so their parents could come along. Next, they arranged a meeting with their teachers to discuss how they could make the school more sustainable.

Over the next few years nearly 200 visitor centres on every continent hosted the exhibition. It’s cheap to print, so we could make new editions on demand. It’s light and easy to ship, so it was shown around the world. But the real key to its reaching a wide public is that it was shown outdoors. It caught people in city centres, botanic gardens and on university campuses.

It was mostly funded from my savings but well-wishers in the UK and US supported the project when we ran aground. It cost just under £100,000 to reach a worldwide audience of some 15 million people during a ten-year tour.

© Mark Edwards – Photo: Illegally logged hardwood, Nigeria. None of the value in this timber goes to the villagers who live in the forests. This is one small example of the estimated US $1.26 trillion lost to corruption, bribery, theft and tax evasion for developing countries per year.

I received an avalanche of emails from visitors, demanding solutions to align human systems and natural systems to create a whole Earth – whole in the senses of both unified and healed. As well as writing to me at the Hard Rain Project, they wrote to politicians. I had sent copies of the Hard Rain book to every Prime Minister and President so my inbox included emails from political leaders. Gordon Brown, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, wrote:

Hard Rain is both a tremendous achievement and an incredibly troubling book to read – an unrelenting catalogue of burnt and barren landscapes, shrunken ice caps and devastated, dislocated lives.

Page by page it conjures up the terrible consequences of unchecked climate change – a human catastrophe that is quite unprecedented in our history, and one that we can no longer afford to deny.

Already, climate change and the competition for natural resources are destroying livelihoods, creating refugees and stoking conflicts right around the world. To allow this disaster to deepen further would be an unforgivable injustice – for whilst it is the richest countries that have caused this degradation, it is the poorest who are suffering its worst effects.

So, if Hard Rain is a photographic elegy it is also an impassioned cry for change. Forceful, dramatic and disturbing, it is driven by what Martin Luther King called “the fierce urgency of now” – and I believe the call for a truly global response to climate change is an idea whose time has finally come.

Working closely with Lloyd Timberlake in the US and Dag Jonzon in Sweden, we began the follow-up to the Hard Rain exhibition: WHOLE EARTH?. It offers solutions in the areas of climate energy, fresh water, oceans and agriculture, but also in areas such as human rights and economic rule-making. It offers some new ways of thinking. And it gets personal. It wants to know what visitors to the exhibition are going to do now.

The current edition of WHOLE EARTH? is designed for universities and colleges. To take the project to a new audience, I invited universities in Europe who booked the project to send their banners on to a partner college in Africa, Asia and South America. We printed 21 editions of the exhibition, and most of these are now travelling in the Majority World. We received wonderful accounts of the exhibition in Zanzibar and Seychelles, but none more remarkable than Dr Lal’s one-man tour of India. Not content with showing WHOLE EARTH? at the University of Kerala where he teaches, he rolled up the banners and travelled by public bus to over 20 other universities and colleges across South India.

As WHOLE EARTH? shows, we have many of the technical solutions. However, as scientists point out, we are failing to take these solutions to scale fast enough to avoid catastrophic damage to the ecosystems we depend on.

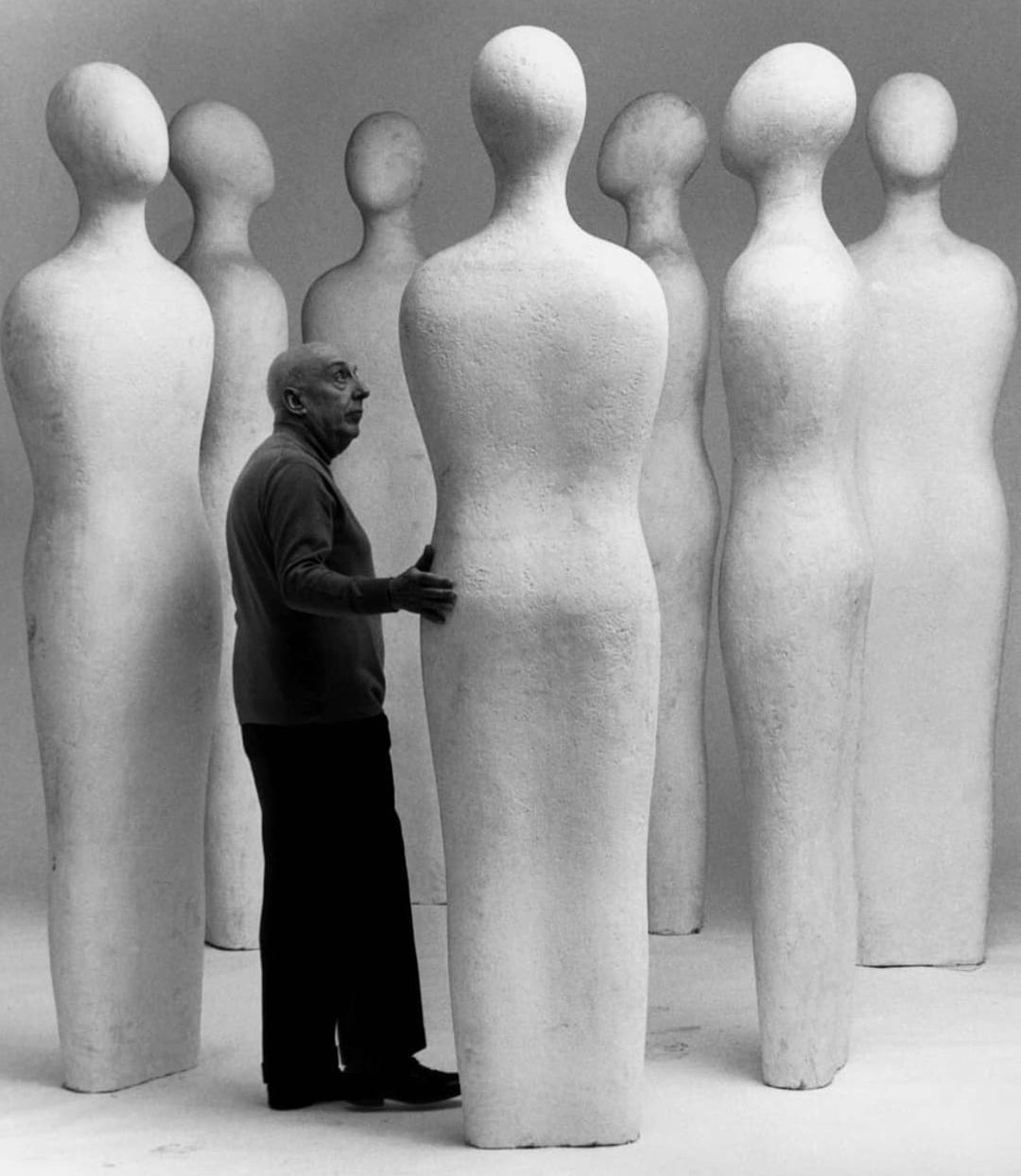

What’s called for right now is a surge of creativity – not just in the sciences, the arts and politics, but in every sphere of human life. A radical transformation along these lines must have taken place in the Renaissance, revolutionising science and ushering in a new view of humanity, culture and society. What is needed today is a new surge that is like the energy generated during the Renaissance but even deeper and more extensive. Creativity is essential if we are to come up with new ways of solving our social, political and environmental problems.

Can we say what creativity is? The minute you try to define it, it slips away. It can’t be cornered. But we can say what it means to be uncreative – caught in a dull, mechanistic way of thinking, defending values that no longer respond to current conditions.

© Mark Edwards – Photo top left: Abandoned bulldozer, Burkina Faso. Photo top right: Gregg Segal – 7 Days of Garbage. Photo bottom left:

Society is good at damping down creativity; its systems of reward and punishment turn us into people constantly looking for approval, instead of risking failure to try out new ideas which may lead to unexpected solutions. Clearly schools have a huge role to play if creativity is to flower throughout life. We need knowledge to pass exams but, as Einstein points out, imagination is far more important than knowledge.

Let’s understand how we got lost as a first step to finding our way. We are a problem-solving species, after all. Can we put aside optimism and pessimism and look at the facts – and stay with the facts? Can we engage a new generation in the transition to a more sustainable society by sharing the mistakes and the solutions they will inherit? Could this approach help spark a creative response that would underpin security for the generation now at schools and universities?

There was a creative wave in the 60s that caught many in my generation. It wasn’t clear what started it; probably a lot of factors came in to play. At that time, there was a feeling that everyone should re-invent their world. It was OK to make mistakes; but not to follow in other people’s footsteps, especially those of our poor, bewildered parents. Of course, we tripped up all the time but we were busy creating what we felt was an exciting, progressive culture, expressed through music, the arts, science and politics.

It swept away the lingering constraints that held society to stale, post-war values and it began to break down some of the class barriers that were so prevalent in Britain.

The publication of Earthrise photo from space played a part in opening up a new way to look at the world and our place in it. For a moment, we were humans first and foremost living on a planet that looked alarmingly fragile.

I’m not suggesting that a photograph changed humanity, but that view of our planet from space was an extraordinary moment that marked the beginning of the contemporary environmental movement. It opened a door to a new way of thinking that put us on the tracks to a more sustainable society.

What can we do to accelerate this transition? First, we must make sustainable development interesting, and that requires imagination. No one, especially students, should have to sit through dull talks or read tedious articles illustrated with dog-whistle photographs. We all have a responsibility to bring the challenges around sustainable development vividly alive. We need to bring brilliant artists and scientists together to infect us all with their sense of wonder and curiosity. As the philosopher, J. Krishnamurti points out, “We can’t be ordinary people anymore; our problems are much too serious.”

Shakespeare, one of the most creative men to have lived, sums up our predicament beautifully:

There is a tide in the affairs of men.

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat,

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

Climate change – a truly global problem, that puts all of us in the same boat, that demands solutions to all our problems as a whole – has given us an extraordinary opportunity to rethink what we really want for ourselves and for the world at large.

Of course, the forces ranged against such a change are formidable. That’s how it is during a transition. It looks impossible – and then it’s not. History shows us over and over again that radical proposals accumulate to a critical mass that succeed in sweeping away existing structures and assumptions.

With this in mind, we are going to make a new exhibition to celebrate and publicize the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The planet’s governments have agreed to deliver 17 UN SDGs by 2030. Reaching those goals is going to require humanity to navigate a political and policy maze, so it is appropriate that our new project (always assuming we get the funding) will be shown in a specially designed outdoor maze.

The Maze will bring alive the SDGs for a wide public around the world. The SDGs require solutions to the problems highlighted in Hard Rain: poverty, hunger, climate change, inequality, and the destruction of ecosystems. These are among the challenges the planet’s governments have signed up to deal with by 2030. Here is an extraordinary example of political leaders and the UN going beyond the dreams of the most ardent campaigners to reinvent the world so that it’s compatible with nature as well as human nature. If they are delivered.

It’s a big if. Though the Millennium Development Goals, which expired in 2016, did inspire progress, they were not globally realized. So, The Maze is not a static look-and-see exhibit, but will be designed to inspire the public, schools and universities to bolster political leaders to actually deliver the SDGs they have signed up to.

The SDGs call for action by all countries – poor, rich and middle-income – to promote prosperity and equity while protecting the planet. Mirroring this international approach, the Maze will launch simultaneously from botanic gardens, universities and visitor centres on each continent, the venues interlinked so that visitors on different continents may communicate with each other.

The uncertain path through The Maze will add a further element of fun and interactivity to the exhibition. The passages the SDGs. Cul-de-sacs show viewers our current problems; taking a wrong turn puts a visitor face-to-face with a sustainability issue in a novel manner. Reaching the core, visitors will see proven solutions – from governments, business, civil society and citizens – that illustrate how the goals can actually be delivered.

The SDGs are ambitious and so is the Hard Rain Project. We are buoyed up by the 2017 UNESCO-Japan Prize and are now determined to find the funding we need to support this extraordinary project.

I hope you will come to the launch, join us in The Maze, get lost, find your way, and leave transformed!

Share this via…

Visit: What’s On

© Sarah Jane Poter – Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nullam vitae mauris non mauris lacinia viverra.

© Sarah Jane Poter – Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nullam vitae mauris non mauris lacinia viverra.