Sandra Taper MSc – June 22, 2021 – 10 min read

Polar bears on thin ice, carbon emissions, rising temperatures, we have all heard of climate change. It is the biggest challenge of our time (and set to get bigger assuming we haven’t already passed the tipping point).

The phenomenon affects us all.

As problematic as it is, however, we cannot ignore the fact that communities in the Global South carry the majority of the burden despite their negligible contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Some might say this could be attributed to ‘unlucky’ geographical placement, others, more persistent constraints such as poverty, inadequate training and education, land right issues, food insecurity and growing inequalities.

Within communities in the Global South, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) women from across the world are becoming increasingly more vulnerable to climate change*. Faced with multiple priorities to ensure the livelihood of themselves and their families, these women are responsible for childcare, housework, food production and collection of fuel and water – all activities which are threatened by climate change. Since little progress has been made to reduce their vulnerability, BAME women have been forced to the forefront of the ever-changing Anthropocene.

*This is not to say that BAME Women are not impacted by climate change elsewhere around the world, but for now I will focus on those in the Global South because they are often the most marginalised group in the community.

Let’s take water as an example. Water is vital for all life on Earth, yet as atmospheric temperatures increase, water scarcity will continue to become a pressing issue. Mismanagement of water resources and more frequent extreme weather events (e.g. droughts) will overwhelm water resources, especially in Sub Saharan Africa and Asia. This will directly impact Women, who are required to walk each day and collect water for domestic use, by making the journey longer and less efficient.

Threats to water resources are also interlinked with water governance, which sees Women often marginalised from decision making at a local level. Low-levels of involvement in decision making can be perpetuated by Women often leaving formal education far earlier than men. And the problems don’t stop there. Threatened water resources also cause sanitation issues which disproportionally affect Women. Inadequate sanitation in certain communities may result in Women participating in open defecation which, in turn, increases their exposure and thus risk to violence and sexual assault.

What exacerbates the problem of inequity further is that Women’s vulnerability is often coupled with a limited capacity to adapt. Those who look after children may be unable to migrate away from climate impacts or disasters. Those who are able to migrate or are displaced, then face further risks of violence and sexual assault, clearly violating their human rights. Whilst these are just a few examples showing how dramatically BAME Women are affected by climate change, it is important to mention that vulnerability is not only determined by gender and that other socioeconomic factors and power relations also result in different experiences of climate impacts.

Either way, it is clear that there is the critical need for climate change mitigation, adaptation and above all else, climate justice.

Is there hope?

Just reading through the news I feel I am overwhelmed with economic climate concerns; Can we make planes green? How can we maintain our levels consumption without reducing our consumption? Who can we blame for emitting the most? At the same time the media is fixated on emotive images of malnourished polar bears and scorched lands in the deserts of the world. Climate change is a complex web of causes and effects which are hard to decipher, and such a multi-faceted issue deserves an equally multi-faceted solution.

Sustainability is based on three pillars; economic, social and environmental. Whilst I fully accept the importance of arctic conservation and desertification (after all, they directly relate to economic and environmental sustainability), what I am more concerned with is the lack of consideration for social sustainability. Here, current gender inequalities are glaringly unsustainable, thus limiting resilience and mitigation of climate change. Sustainability has become fixed on the international agenda since the famous “Our Common Future” report in 1987. A big milestone took place in 2015 when the UN released the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs provide a series of targets and objectives for all nations to reach by 2030.

Regarding BAME Women and climate change, multiple SDGs are relatable, however SDG 5 – gender equality – is a crucial objective which now more than ever needs careful consideration. UNESCO plans to meet this by strengthening multi-stakeholder partnerships involving governments, civil society, private sectors and academia. This would lead to positive outcomes because it promotes inclusivity of a diverse range of interested parties at multiple institutional levels. It also moves away from a centralised, top-down approach to a more grass-root, bottom-down approach to projects. This reduces the risk of imposing westernised values upon reluctant communities in the Global South.

The agenda also mentions gender mainstreaming. Focus on gender mainstreaming is vital because, currently, many NGOs and governments do not realise the importance it holds for BAME Women in the Global South and their involvement will become imperative the more climate change progresses. That being said, gender mainstreaming is not a fix-all solution as we must go beyond giving power to BAME Women because power does not automatically translate to meaningful involvement in the decision-making process. This is arguably because of the existing power dynamics within communities and institutional bodies that often favour the voices and opinions of men.

So what can be done?

Gender equality and female empowerment is essential for ensuring that BAME Women in the Global South do not become more vulnerable to climate change. However, while sounding promising on paper, when applied on the ground the reality may be different. Sustainable development polices and projects have to overcome social barriers BAME Women have faced for a very long time. Any sustainable development project should aim to use a community-based approach and promote collective action. Approaches like these keep external influence minimal and allow communities themselves to lead the decision-making process.

Beyond this, interventions need to make sure that projects are sustained long-term and refrain from allowing communities to slip back into old ways, which in turn impairs social development. One way of ensuring this is by acknowledging the importance of monitoring and evaluation of projects once successfully implemented to ensure change is maintained. This should allow BAME Women to participate in leadership and decision-making concerning climate change action and under this, consideration for food security, economic security and health.

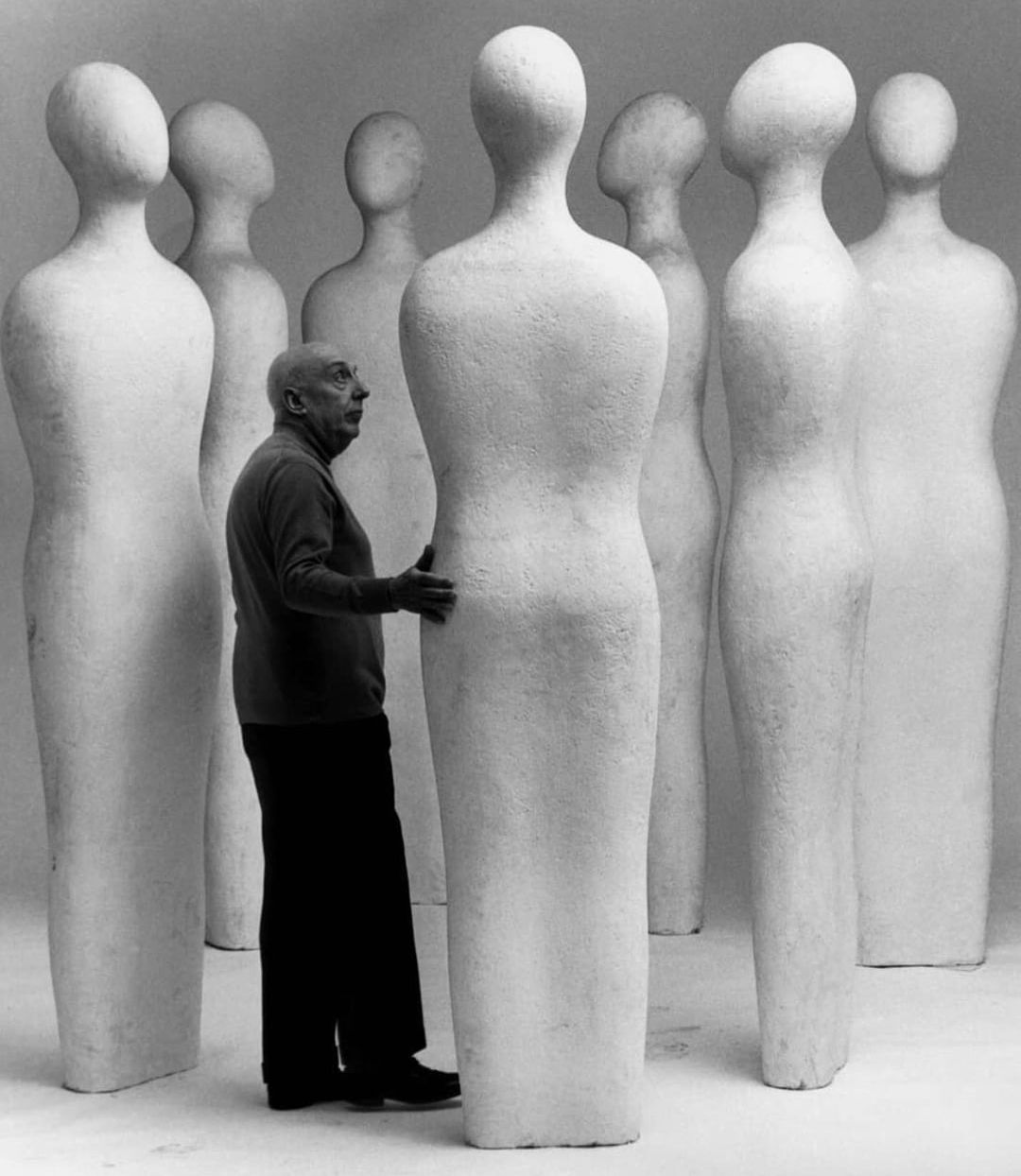

It is now more important than ever to ensure the voices of BAME Women are not silenced. They are the inherent pillars of communities around the world and yet are often misrepresented. Climate change is gendered. It is gendered more towards men as they are often the ones with the authority to make decisions while marginalising Women, which exacerbates the patterns of inequality. To ensure that the SDG targets are met, more needs to be done to get the ball rolling beyond what is on paper and implement these objectives and values on the ground, particularly in the Global South. Women are a goldmine of resources and it’s about time we acknowledge this.

Sandra Taper, Scientific Officer at APHA, International Development: Environment and Climate Change MSc.

The views contained in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the UK National Commission for UNESCO or UK Government.

Share this via…