Series: Heritage and Our Sustainable Future

Issue 3; 26th July 2021

Brief reports are released throughout the year. Check out the complete* series below!

*subject to release date

ISSN 2752-7026

01

1 Capacity strengthening constitutes a cross-cutting approach towards sustainable development, and is essential to meet each SDG.

Capacity development needs to be implemented holistically, integrating all dimensions of sustainable development (social, economic, environmental) and all actors involved (researchers, practitioners, policymakers, communities). The relationship between heritage, people, and places should be at the core of research, policy, and action to strengthen capacities for global development.

2Individuals, communities, and institutions have different capacities, and there are multiple ways of sharing knowledge and contributing to capacity development.

Capacity strengthening is a concept that goes beyond transferring knowledge or providing training. It is a continuous process of mutual learning and understanding, empowerment of others, and relationship strengthening between different actors and institutions.

02

1 Capacity strengthening constitutes a cross-cutting approach towards sustainable development, and is essential to meet each SDG.

2Individuals, communities, and institutions have different capacities, and there are multiple ways of sharing knowledge and contributing to capacity development.

03

Heritage is facing global threats and risks. Damaging actions and practices as well as management and institutional issues are amongst the most important threats to the conservation and protection of heritage sites.

The heritage community is not well prepared to tackle global challenges. There is a gap between the academic training received by heritage professionals, and the actual realities on the ground, which require more interdisciplinary approaches, going beyond individual academic expertise.

Heritage practitioners are still strongly entrenched in conventional ‘Western’ conservation approaches, underestimating the potential of Indigenous and local knowledge and practices.

Some languages (particularly English and French) are predominant in the heritage sector, constituting barriers to inclusion and meaningful participation. Moreover, different sectors and actors use different expressions, terminologies, and meanings when referring to similar concepts.

Capacity strengthening is not only related to formal education, learning, and training, but is the wider process through which individuals, organisations and societies obtain, strengthen, and maintain capacities to set and achieve their own development objectives over time.

04

Through international partnerships, the Science Museum Group extends its mission to inspire futures beyond our walls and develops capacity in our sector. This case study illustrates these drivers and demonstrates our commitment to equity and sustainability. Superbugs: The Fight For Our Lives is an exhibition about antibiotic resistance, an existential threat to humankind. It explains the issues, demonstrates the impact of individual behaviours, and illustrates the global scientific effort to combat the problem. After showing at the Science Museum in 2017/18, it toured via a “Blueprint pack”—only intellectual property travels, no artefacts or structures, and the exhibition is adapted by each venue for the local context. It is both cheaper to hire and more sustainable than a conventional exhibition. Superbugs primarily speaks to SDG 3, Good Health, but it also supports education, careers, innovation, and partnership (SDGs 4, 8, 9, and 17).

Beyond London, over 1.5 million people engaged with the project in China, India, Argentina, Russia, South Korea, Mexico, and the USA. As well as visitors’ enjoyment and learning, the partners widened and deepened understanding about exhibition-making, audience engagement and innovative collaboration. Superbugs in India and China was supported by Wellcome and the British Council.

Helen Jones, Director of Global Engagement and Strategy, Science Museum Group (UK)

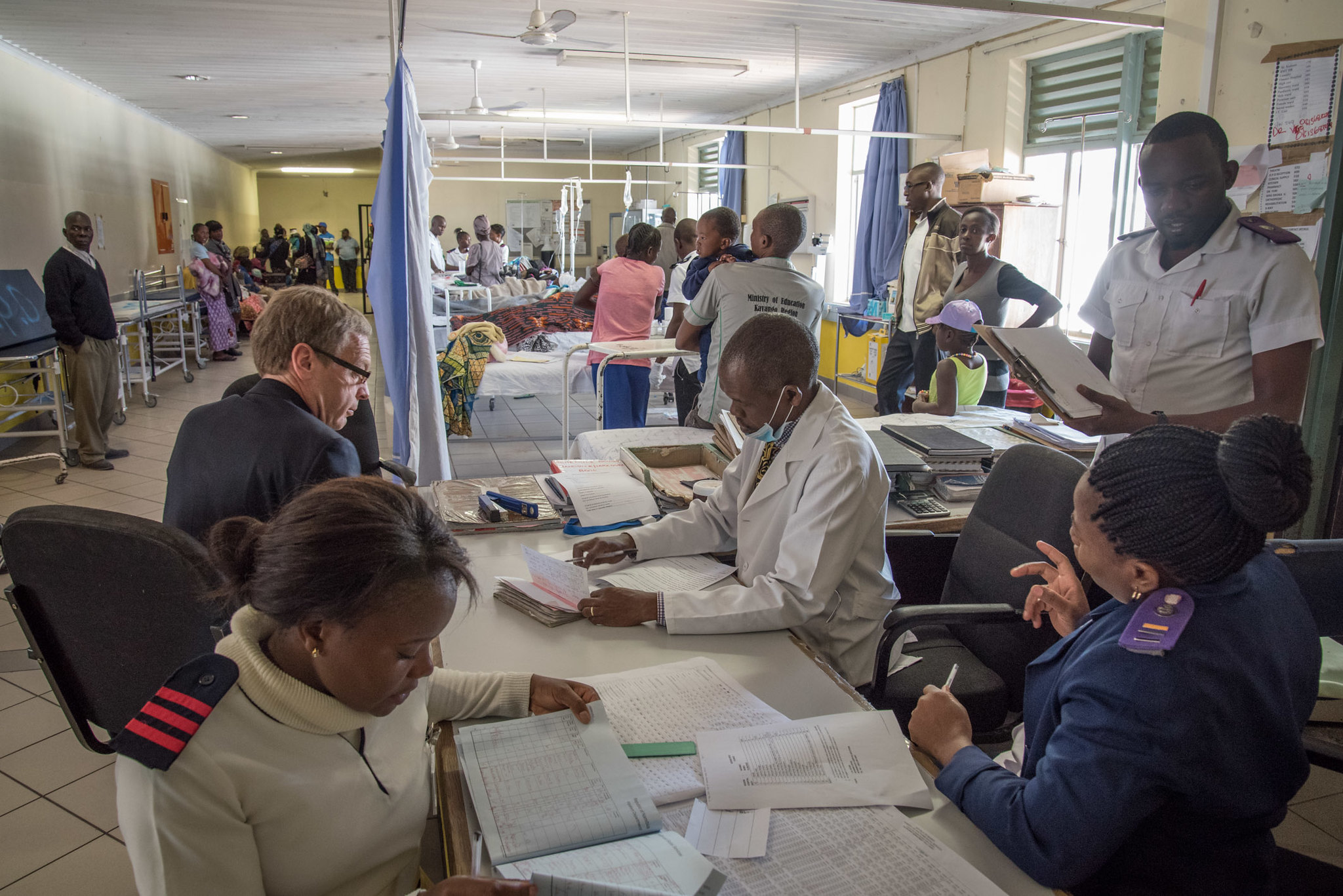

Equal access to education and inclusive public communication are significant challenges in Namibia – a nation which, with some 30 languages, is characterised by linguistic and cultural superdiversity. Working collaboratively through the Transnationalizing Modern Languages: Global Challenges project and Cardiff University’s The Phoenix Project, supported by the Welsh Government, a group of specialists in languages, health, and education addressed the need for greater understanding of the connection between multilingualism, cultural heritage, and social development.

The goal of the project was to design tools that would foster a widespread understanding of the importance of language as a resource for the promotion of individual and collective well-being as well as inclusive forms of social change. The project focused on educators and health specialists, aiming to develop culturally sensitive approaches to professional training and pedagogic practices. Its outcomes to date include the integration of a language component focusing on indigenous languages in the MMed-Anesthesia launched by the University of Namibia in 2018. In a country which was until recently mainly dependent on expatriate medical specialists, this move to underscore the usefulness of indigenous languages for the health sector is a remarkable step towards recognising the value of cultural heritage.

A move away from language indifference—the tendency to ignore the impact of language choices on equality, diversity, and accessibility—and towards greater linguistic awareness is also a move towards valorising heritage as a future-making resource, thereby leading to more effective education and public communication, and, ultimately, to greater social cohesion and social justice.

Dr Nelson Mlambo, Senior Lecturer, Department of Languages and Literature Studies, University of Namibia; Prof Loredana Polezzi, Alfonse M. D’Amato Chair in Italian American and Italian Studies, Department of European Languages, Literatures and Cultures, Stony Brook University & Honorary Chair, School of Modern Languages, Cardiff University; Judith Hall, Phoenix Project Lead, Cardiff University

From the analysis of World Heritage State of Conservation reports, management and institutional factors are ranked amongst the highest threats for heritage conservation. The factors hindering effective site management come more and more from beyond the confines of the site. However, our own actions and practices are mainly confined to the boundaries of the heritage designation, and are unable to deal appropriately with the changes facing heritage. The way that we perceive the division between nature and culture hinders our holistic approach towards managing heritage, as does the way that we are trained as professionals. We are trained in a specific field of heritage, such as archaeology, biology or conservation science, and yet the issues and realities of managing a site go beyond these disciplines and are interconnected within the place. The approach adopted by the World Heritage Leadership Programme is to provide capacity strengthening activities for heritage site managers on the necessities of adopting a heritage place approach. The programme provides a framework, where heritage is situated within an environmental, social, and economic context with people, and is impacted by and causes impacts on different facets of that place. This enables us to be successful in both heritage conservation and in achieving SDGs. However, we need to recognise that the capacity to change our way of working resides in various actors like heritage practitioners, institutional frameworks, communities, and networks, and that capacity development must address all of these audiences.

Eugene Jo, Programme Manager, World Heritage Leadership Programme, ICCROM-IUCN

UK National Commission for UNESCO

[email protected]

Prof Stuart Taberner, Director of the Frontiers Institute, and Principal Investigator at PRAXIS, University of Leeds, UK

Dr Francesca Giliberto, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow on Heritage for Global Challenges at PRAXIS, University of Leeds, UK.

Helen Maclagan OBE, Former Vice-Chair and Non-Executive Director, UK National Commission for UNESCO; Dr Esther Dusabe-Richards, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at PRAXIS, University of Leeds, UK.

Matilda Clark, Project Officer, UK National Commission for UNESCO; Matthew Rabagliati, Head of Policy, Research and Communications, UK National Commission for UNESCO.

Eugene Jo, Programme Manager, World Heritage Leadership Programme, ICCROM-IUCN; Dr Nelson Mlambo, Senior Lecturer, Department of Languages and Literature Studies, University of Namibia; Prof Loredana Polezzi, Alfonse M. D’Amato Chair in Italian American and Italian Studies, Department of European Languages, Literatures and Cultures, Stony Brook University & Honorary Chair, School of Modern Languages, Cardiff University; Judith Hall, Phoenix Project Lead, Cardiff University; Helen Jones, Director of Global Engagement and Strategy, Science Museum Group, UK.