Discover Policy Brief

n°17

UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage

Protecting and preserving our underwater cultural heritage continues to be a vital global issue, and there has been growing pressure on the UK government to act. In the light of the growing number of countries that have ratified the UNESCO Convention on Underwater Cultural Heritage, this brief considers options for the UK.

The Underwater Cultural Heritage Convention was adopted in 2001 in Paris, and is not ratified by the UK

This policy brief proposes that ratifying the 2001 Convention could provide the UK with an opportunity to influence the evolution of good practice in the management of underwater cultural heritage (UCH) internationally, to deploy and develop the acknowledged world-class expertise of UK professionals in UCH, and to broaden opportunities for these professionals to apply and share their skills and knowledge globally. It also addresses reservations the UK had at the in 2001 and explains why they may no longer be a concern.

Read Policy Brief

n°17

01

Executive Summary

Underwater Cultural Heritage is a live issue and there is growing pressure on the UK government to act. In the light of the conclusion of the recent Impact Review 1 and the growing number of States who have ratified the UNESCO Convention, it is timely for the UK government to revisit its position.

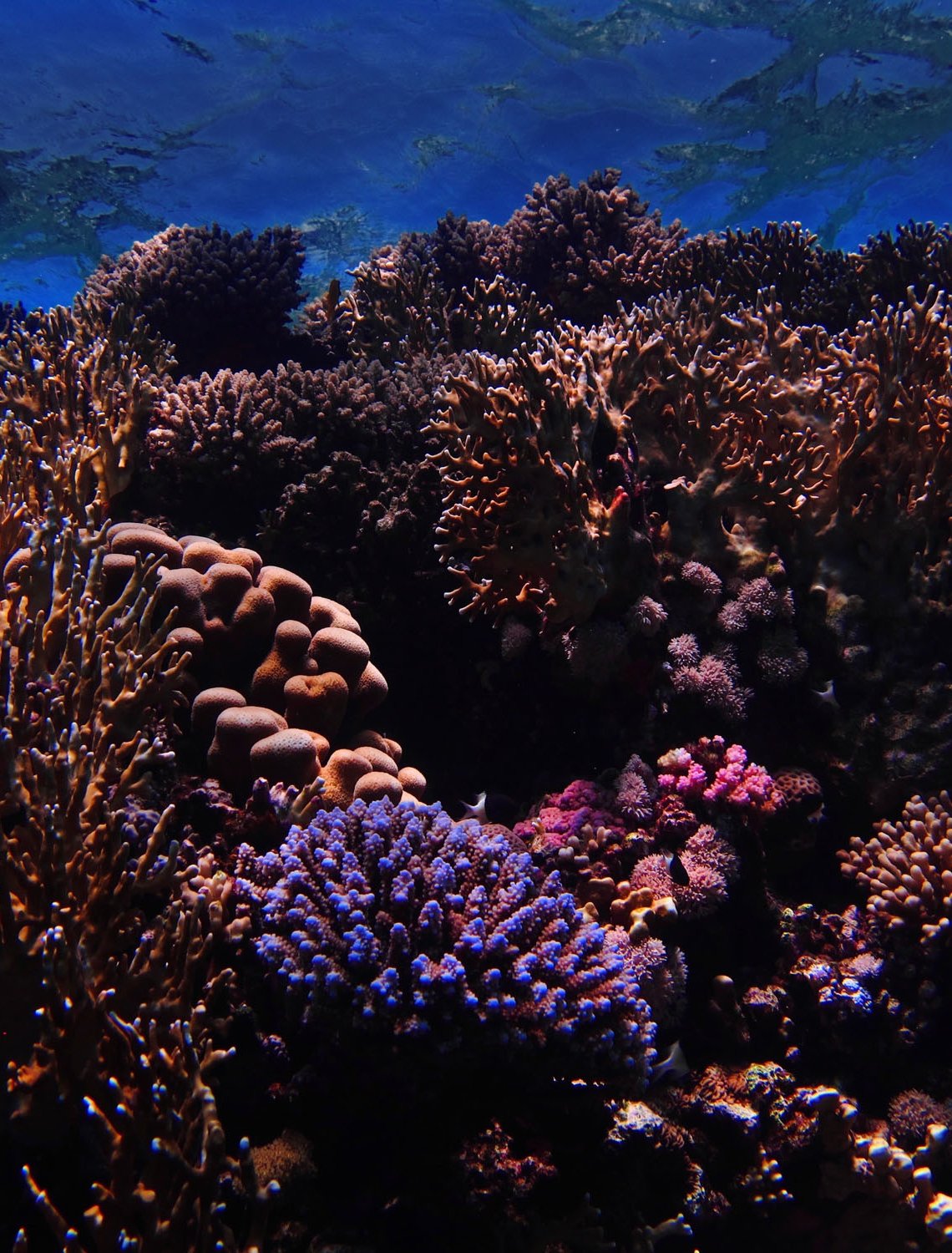

Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) refers to traces of human existence which have been partially or totally underwater, periodically or continuously for at least 100 years. It forms an integral part of a common global archaeological and historical heritage and can provide invaluable information about culture, economies, migration, and societal inter-relationships.

A Briefing Note by the British Academy and Honor Frost Foundation published in 2014 explicitly makes the case for UK ratification, noting that the Impact Review has demonstrated that the UK’s 2001 reservations need no longer be such a concern.

There are a number of broader developments and factors in relation to the Convention and the international and domestic management of underwater archaeology which are important to take into account.

→

The UK has adopted ‘The Rules’, an Annex to the Convention, which includes the principle that UCH should not be commercially exploited.

→

It is already government policy that marine licences must comply with ‘The Rules’.

→

A number of other major maritime States who originally had concerns about the Convention have now ratified including Spain, France, and Portugal. The Republic of Ireland, Germany and the Netherlands are all considering ratifying.

→

The Convention distinguishes between activities directed at UCH, and those which incidentally affect UCH. The scope is therefore narrower than might be presumed.

→

The UK will not automatically be required to protect all wrecks in its territorial seas.

→

The UK will not automatically be required to protect all wrecks in its territorial seas.

→

There are several business sectors in the UK which could gain internationally from full UK participation.

→

The 2001 Convention is increasingly becoming established as the principal framework for international law for underwater archaeology.

Should the government choose to move towards ratification, consultation with those members of the maritime community who are concerned about its potential impact on their activities could usefully seek to identify and address any remaining substantiated concerns.

The Review found that the majority of the substantive clauses of the 2001 Convention appear to present no difficulty to the UK, and that the UK has world-leading experience in some particular areas. However there are some clauses which would require the UK to introduce new measures in policy and administration, and potentially in law, and to reallocate resources:

→

Regulation or removal of UCH from salvage law

→

Development of reporting/notification mechanisms

→

Provision for seized UCH

→

Human Remains

→

Archaeological Archives

Recommendations

The UK government should:

→

reevaluate whether it should ratify the Convention and

→

as a first stage, conduct an inter-departmental regulatory impact assessment, involving the Ministry of Defence (MoD), the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and any other relevant departments, to define the legal and administrative changes and resources required, including issues identified in relation to human remains, archaeological archives and salvage.

1 Full report: February 2014 ‘The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001. An Impact Review for the United Kingdom Final Report’ ISBN 978-0- 904608-03-8

02

Background

Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) refers to traces of human existence which have been partially or totally underwater, periodically or continuously for at least 100 years. It forms an integral part of a common global archaeological and historical heritage and can provide invaluable information about culture, economies, migration, and societal inter-relationships. The United Kingdom has a varied and rich UCH and world-leading expertise. In 2001 the General Conference of UNESCO voted to adopt the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. The Convention came into force in January 2009. It has since been ratified by 49 2 States and is a key feature of the international framework for the management of UCH.

The UK was one of a number of States that abstained from the 2001 vote and has not ratified the Convention. In the UK’s Territorial Sea, UCH is protected by domestic law, policy and practice. But threats continue to grow to UCH in international waters, adjacent to the coast of the UK and elsewhere in the world, in which the UK has an interest. The issue of how to protect and preserve UCH beyond the UK’s Territorial Sea is a live debate which needs addressing.

In 2012 a multi-disciplinary project team – the UK UNESCO 2001 Convention Review Group – brought together experts with relevant specialisms from universities, practitioners, English Heritage and professional bodies to undertake an Impact Review for the United Kingdom. The project was funded by English Heritage and the Honor Frost Foundation and was administered by the United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO. The purpose of the Review was not to advocate ratification, but to examine what ratification might mean, bearing in mind the concerns raised in 2001.

Building on the Impact Review, in March 2014 the British Academy / Honor Frost Foundation Steering Committee on Underwater Cultural Heritage called on the UK Government to ratify the Convention, and published a Briefing Note setting out the case for so doing. This position has widespread support particularly from the academic and professional community; within some elements of the maritime community there is still debate as to the pros and cons of ratifying. This briefing summarises the issues and makes recommendations for a way forward for the UK government.

2 Number of ratifications in February 2015

03

Building the case for ratification

3.1 The Impact Review 3

The Review revisited the UK government’s concerns of 2001 in the light of present circumstances, considered the legal, policy and administrative implications, were the UK to ratify the Convention, provided a clause-by-clause examination of the Convention, identifying any which could cause a difficulty for the UK. The table below sets out the four issues cited by the Government in 2001 and the corresponding findings of the Impact Review.

3.2 British Academy and Honor Frost Foundation key reasons

The British Academy and Honor Frost Foundation Briefing Note explicitly makes the case for UK ratification.5 Noting that the Impact Review has demonstrated that the UK’s 2001 reservations need no longer be such a concern, the Note sets out 5 key reasons to ratify:

1

Protection for historic wrecks of UK origin around the world, including the wrecks of warships, other state vessels, and ships with which the UK declares a ‘verifiable link’

2

Increased international recognition of UK interests in wrecks that originated here and easier management of underwater cultural heritage;

3

Reduced costs from streamlining existing ad hoc arrangements and benefits from recognising that UCH is a valuable social and economic resource;

4

Enhanced opportunity for the UK to reinforce its interpretation of the international Law of the Sea and to make its case within the Convention’s own institutions;

5

Increased role and recognition and opportunities for growth of the UK heritage sector internationally, where there is expanding global demand.

3.3 The broader context

There are a number of developments and factors in relation to the Convention and the international and domestic management of underwater archaeology which are important to take in to account. These include:

→

Since 2008 the UK has adopted ‘The Rules’, an Annex to the Convention which sets out a standard for archaeological investigations, as government policy for UCH. The principle that UCH should not be commercially exploited has thus already been accepted and it is already government policy that marine licences must comply with ‘The Rules’.6

→

A number of other major maritime States who originally had concerns about the Convention have now ratified including Spain, France, and Portugal. The Republic of Ireland, Germany and the Netherlands are all considering ratifying.

→

The Convention distinguishes between activities directed at UCH, and those which incidentally affect UCH. The scope is therefore narrower than might be presumed.

→

The UK will not automatically be required to protect all wrecks in its territorial seas.

→

There are several business sectors in the UK which could gain internationally from full UK participation.

→

The 2001 Convention is increasingly becoming established as the principal framework for international law for underwater archaeology. The UK is a world leader in several aspects of UCH, academically and professionally; ratification would increase opportunities for international influence.

The UK’s maritime heritage is worldwide, deriving from the largest merchant fleet, and the most prolific shipyards. For those lost at sea, wrecks are their last resting places. The ‘verifiable links’ of the Convention offer some protection for UK interests beyond the UK’s own waters, including consultation in respect of discoveries and proposed investigations, and appropriate treatment for human remains and historical evidence. This means the UK must be consulted even where the ‘interest’ arises not merely from proprietary rights, such as ownership or derogation in insurance but where the link is merely cultural in nature such as country of origin of cargo or crew.

3 Full report: February 2014 ‘The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001. An Impact Review for the United Kingdom Final Report’ ISBN 978-0- 904608-03-8

4 The UNCLOS codifies a series of maritime jurisdictional zones. The 2001 Convention seeks to provide greater clarity about how UCH is protected by states within each zone. See Appendix, Abbreviations and Definitions for details of zones.

5 The 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The case for UK ratification. The British Academy and Honor Frost Foundation, March 2014

6 The Rules concerning activities directed at underwater cultural heritage, Annexed to the 2001 Convention

04

Concerns expressed about ratification

The maritime archaeological community is not united in its support for Ratification of the Convention; there are some who are opposed outright, and others unsure of the benefits.7

Arguments against ratification include concerns that it would adversely affect particularly those working in a non-professional or commercial capacity including: placing undue restrictions on those wishing to excavate underwater heritage; excluding those not qualified as marine archaeologists from monitoring and surveying work, and having a negative impact on salvage, perhaps creating a black market. (It has also been suggested that many more wrecks would need to be designated – this point has been addressed above.)

In this context the following points should be noted. The UK adoption of ‘The Rules’ of the Convention as UK policy for managing underwater heritage means that there would be no significant change in the procedures and permissions affecting activities directed at underwater sites if the UK were now to ratify the Convention. Monitoring and surveying activities are not ‘activities directed at’ UCH within the meaning of the Rules and for this reason are not required to

be supervised by a qualified marine archaeologist. Similarly, salvors are already subject to the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 / Marine (Scotland) Act 2010. Ratifying the 2001 Convention would therefore add no further change to the UK’s current position, nor impose significant additional restrictions.

Nonetheless, there are strongly held and expressed views on these matters. Should the government choose to move towards ratification, consultation with those members of the maritime community who are concerned about its potential impact on their activities could usefully seek to identify and address any remaining substantiated concerns. The Impact Review looked specifically at the legislative, policy, resource, and administrative changes that might be required if the UK were to ratify the Convention.

The Review found that the majority of the substantive clauses of the 2001 Convention appear to present no difficulty to the UK, and that the UK has world-leading experience in some particular areas. However there are some clauses which would require the UK to introduce new measures in policy and administration, and potentially in law, and to reallocate resources:

7 World Archaeology: http://www.world-archaeology.com/latest-posts/how-should-we-protect-our- sunken-heritage.htm

05

Issues to resolve

The Impact Review looked specifically at the legislative, policy, resource, and administrative changes that might be required if the UK were to ratify the Convention.

The Review found that the majority of the substantive clauses of the 2001 Convention appear to present no difficulty to the UK, and that the UK has world-leading experience in some particular areas. However there are some clauses which would require the UK to introduce new measures in policy and administration, and potentially in law, and to reallocate resources:

The regulation or removal of UCH from salvage law

In the UK, UCH is not exempt from the application of salvage in common law or statute, and the common law property rights of salvor in possession are also applicable. Options set out in the Impact Review 8 to achieve compliance with Article 4 of the Convention (which requires that activities directed at underwater cultural heritage shall not be subject to the law of salvage or law of finds unless they meet certain criteria 9) include policy and administrative measures such as:

→

the UK government to decide not to engage in salvage-based contracts in respect to UCH;

→

the amount of salvage paid to be based on the extent of protection;

→

the UK government make a reservation as in the case of the IMO International Convention on Salvage (1989).

Alternatively, primary legislation could remove underwater cultural heritage from the application of salvage law.

Development of reporting/notification mechanisms

The Convention introduces the need for a series of formal administrative mechanisms to notify and in some cases consult with other States Parties (flag States / States with verifiable links), and to notify the Director-General of UNESCO and the Secretary-General of the International Seabed Authority in specific circumstances: these are mainly in respect of discoveries of UCH or where there is the intention to engage in activities directed at UCH. Such notification and consultation may well already be taking place case-by-case, but it would be helpful (and probably more cost-efficient) if it were placed on a systematic basis taking into account the devolved character of the management of UCH in the UK Marine Area.

Provision for seized UCH

Some reallocation of resources may be required to provide contingency arrangements for UCH in the UK which has been recovered in a manner not in conformity with this Convention and which is seized under Article 18(1). This may simply mean that arrangements that are currently made case-by-case are formalised in order to demonstrate compliance.

Human remains

The 2001 Convention requires provision for proper respect for human remains which may lie within wrecks. This is an issue on which public opinion can run high; the centenary of the start of World War I, and burgeoning interest in family history, is likely to increase attention to this aspect of wrecks. Current UK legislation (The Burial Act 1857) is on its own inadequate to achieve compliance as it applies to ‘Places of Burial’, and thus does not generally cover human remains at sea. Discussions around better provision for remains at sea (which is already an issue domestically) are under way. Meanwhile, compliance with the requirement of the Convention (Article 2.9) to ‘ensure proper respect’ could probably be achieved by extension and amendment of existing professional codes of ethics, practice and guidance on the treatment of human remains.10

Archaeological archives

Although there are examples of very good provision being made for the long- term preservation of archives, the UK does not have comprehensive provision overall to satisfy this clause. This is an identified weakness in the management of underwater cultural heritage domestically, requiring clarification of roles and responsibilities and support for the development of suitable repositories.

Other areas of the 2001 Convention which might appear problematic are addressed by the UK’s commitment to implement the Rules annexed to it, although further steps may be required to ensure that this commitment is thoroughly understood and given effect throughout Government. The Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 / Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and the Dealing with Cultural Objects (Offences) Act 2003 already provide a statutory basis for implementing many clauses of the 2001 Convention, especially in the EEZ / Continental Shelf, extra-territorially (e.g. in the EEZ / Continental Shelf of other countries) and in denying support to others carrying out activities not in conformity with the Convention.

8 February 2014 ‘The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001. An Impact Review for the United Kingdom Final Report’ pp 73-75

9 Article 4: Relationship to law of salvage and law of finds. Any activity relating to underwater cultural heritage to which this Convention applies shall not be subject to the law of salvage or law of finds, unless it: a) is authorized by the competent authorities, and b) is in full conformity with this Convention, and c) ensures that any recovery of the underwater cultural heritage achieves its maximum protection.

10 E.g. http://www.culturalpropertyadvice.gov.uk/public_collections/human_remains

06

Conclusion

Underwater Cultural Heritage is a live issue and there is growing pressure on the UK government to act. In the light of the conclusion of the Impact Review and the growing number of States who have ratified the UNESCO Convention, it is timely for the UK government to revisit its position.

The Impact Review provides detailed analysis of the evidence surrounding the four concerns originally cited by the UK government. It concludes that these issues are no longer as problematic as they might have appeared in the closing stages of negotiating the Convention:

→

The Convention has proved compatible with UNCLOS.

→

The UK position on Sovereign Immunity, in relation to sunken warships, aircraft and state vessels, is not compromised – indeed is in part strengthened – by the Convention.

→

The numbers of known wrecks, and likely activities directed at UCH, is likely to be significantly lower than estimated in 2001, and the Convention is no obstacle to the UK’s preferred approach of significance-based management.

→

Changes in UK domestic provisions mean that the UK is already compliant with many aspects of the 2001 Convention.

The UK has a maritime heritage to be proud of. Ratifying the 2001 Convention could provide the UK with an opportunity to influence the evolution of good practice in the management of UCH internationally, to deploy and develop the acknowledged world-class expertise of UK professionals in UCH, and to broaden opportunities for these professionals to apply and share their skills and knowledge globally.

There are specific issues, discussed above, which require further attention. There are also some dissenting voices in the maritime archaeological community: these need to be heard, and their concerns understood and explored, in any next stage.

07

Recommendations

The UK government should:

→

reevaluate whether it should ratify the Convention and

→

as a first stage, conduct an inter-departmental regulatory impact assessment, involving MoD, DCMS, FCO, MoJ and any other relevant departments, to define the legal and administrative changes and resources required, including issues identified in relation to human remains, archaeological archives and salvage.

UK Marine Acts relevant to UCH:

Protection of Wrecks Act 1973

Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

Merchant Shipping Act 1995

Dealing with Cultural Objects (Offences) Act 2003 Marine (Scotland) Act 2010

Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009

Acknowledgements

This policy brief was produced for the UK National Commission for UNESCO by Helen Maclagan, UKNC Director for Culture; with expert input from John Gribble, Director for Sea Change Heritage Consultants Limited; Mike Williams, Visiting Research Fellow for Plymouth University, and Sue Davies, Cultural Heritage Consultant. The UKNC staff lead was Moira Nash.

The views contained in this policy brief are those of the UK National Commission for UNESCO and do not necessarily reflect those of the UK Government or the individuals or organisations who have contributed to this report.

The Impact Review was funded by English Heritage and the Honor Frost Foundation and managed by John Gribble. Andrea Blick and the UK National Commission for UNESCO acted as Project Executive.

The UK UNESCO 2001 Convention Review Group created to undertake the Impact Review brought together a multi-disciplinary team and comprised: John Gribble (Director, Sea Change Heritage Consultants Limited); Dr Antony Firth (Director, Fjordr Limited); Mike Williams (Honorary Professor, Institute of Archaeology, University College London and Visiting Research Fellow, Plymouth Law School, University of Plymouth); David Parham (Senior Lecturer: Maritime Archaeology, Bournemouth University); Dr Simon Davidson (Coastal and Marine, Wessex Archaeology); Tim Howard (Policy Manager, Institute for Archaeologists); Dr Virginia Dellino-Musgrave (Maritime Archaeology Trust); Ian Oxley (Historic Environment Intelligence Analyst (Marine), English Heritage); and Mark Dunkley, (Maritime Designation Adviser, English Heritage). The list of Royal Navy losses between 1605 and 1945 was created by Jessica Berry of the Maritime Archaeology Sea Trust.

Joan Porter MacIver, Executive Director of the Honor Frost Foundation provided invaluable support and assistance in the Review’s production.

The Impact Review benefited from extensive consultation, both in the UK and internationally, in the cultural heritage and legal sectors.

Abbreviations and Definitions

The Ratification Process

? Browse #PolicyBriefs

Enhancing and Harmonising the Strategic Management of UNESCO’s Goodwill Ambassador Programme

AUGUST 2013

#PolicyBrief n°11

An evaluation of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission’s role in global marine science and oceanography

FEBRUARY 2015

#PolicyBrief n°13

The UK National Commission for UNESCO’s Policy Advice

We work with world-leading experts to advise the UK and devolved governments on UNESCO-related issues and to shape UNESCO’s programmes

From analysing global education goals to practical steps to implement UNESCO’s Recommendations, our advice helps ensure UNESCO’s work is effective and UK governments can fulfil their commitments as members of UNESCO