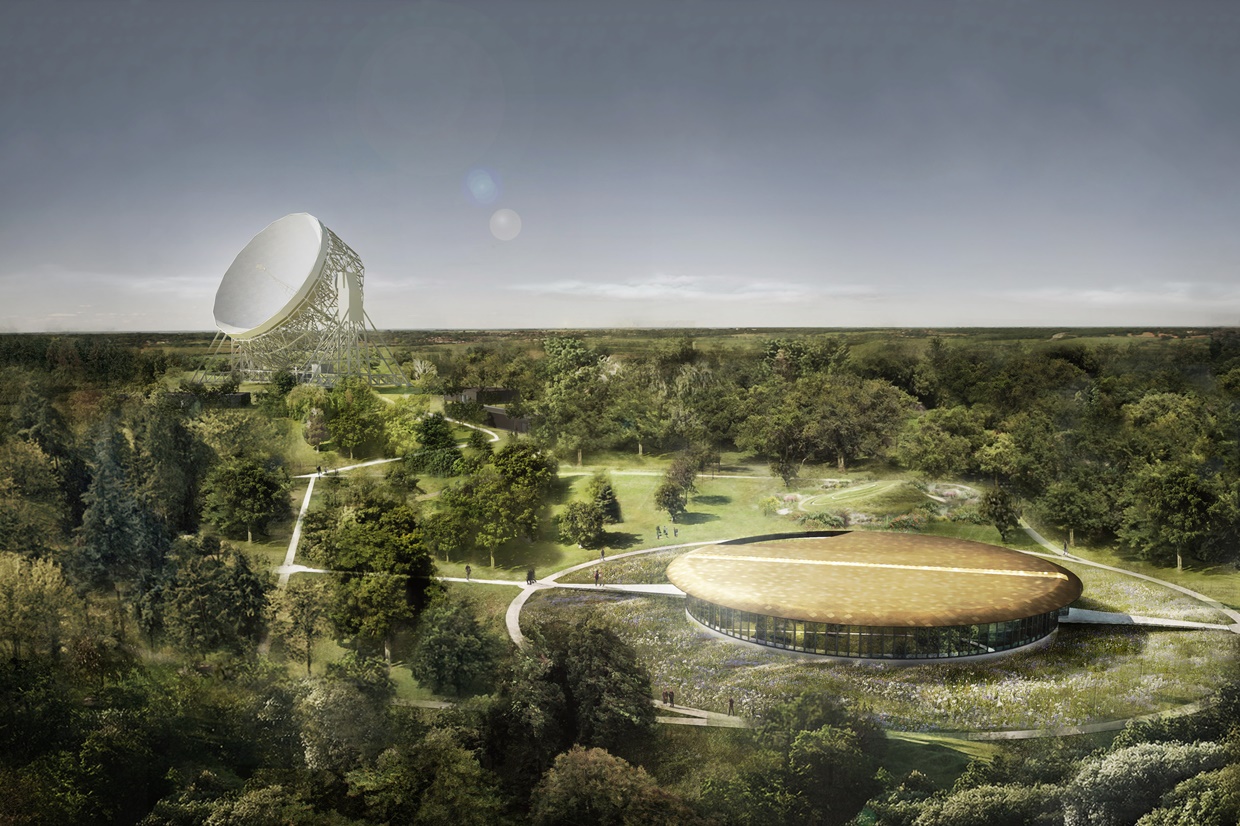

Jodrell Bank is the first 20th-century Observatory on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

There is little doubt that astronomy has played an integral part in the development of humankind.

Archaeological evidence shows that for at least 35,000 years people have observed certain celestial phenomena and reflected about the spatiotemporal structure of the world they perceived themselves as dwelling within.

Traces of very early systems of time-reckoning and visions of the cosmos can be found in caves and sites around the world.

READ ABOUT WORLD HERITAGE SITES OF ASTRONOMY

GIRLS NIGHT OUT MOON SPECIAL

Girls Night Out is one of Jodrell Bank’s many events, returning this October with a special focus on the 50th anniversary of the first explorers on the Moon.

It is the world’s first 20th-century astronomical-related site to be added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site list.

WHY ASTRONOMY AND UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE?

Including the interpretation of the sky as a theme in World Heritage is a critical step toward taking into consideration the whole relationship between mankind and its environment. This step is necessary for the recognition and safeguarding of cultural properties and of cultural or natural landscapes that transcribe the relationship between mankind and the sky.

Properties relating to astronomy stand as a tribute to the complexity and diversity of ways in which people rationalised the cosmos and framed their actions in accordance with that understanding. This includes, but is by no means restricted to, the development of modern scientific astronomy. This close and perpetual interaction between astronomical knowledge and its role within human culture is a vital element of the outstanding universal value of these properties. These material testimonies of astronomy, found in all geographical regions, span all periods from prehistory to today.

[mapsvg id=”5660″]

DISCOVER STONEHENGE

Not only Stonehenge, but many of the 700 archaeological features have been deliberately aligned along the midwinter sunset-midsummer sunrise including the famous Avenue, Coneybury henge, Durrington Walls, and Woodhenge. It was only in the 18th century that the antiquarian William Stukeley rediscovered the axial alignment of Stonehenge upon midsummer sunrise. Archaeological evidence has also shown that the communities lived there in line with seasonal processions and rituals.

Interestingly, the discovery that the Stonehenge Avenue seems to overlie natural geological striations in the landscape, which are themselves aligned along the midwinter sunset-midsummer sunrise solstitial axis, suggests that what seems to us an accident of nature may, for Neolithic people, have provided the ultimate cosmological confirmation of the special nature of this place.

The design, position and interrelationship of the monuments and sites are evidence of a wealthy and highly organised prehistoric society able to impose its concepts on the environment. An outstanding example is the alignment of the Stonehenge Avenue (probably a processional route) and Stonehenge Stone Circle on the axis of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset, indicating their ceremonial and astronomical character.

Since the 12th century, when Stonehenge was considered one of the wonders of the world by chroniclers such as Henry of Huntington and Geoffrey of Monmouth, it has excited curiosity and speculation. It has influenced generations of antiquarians, archaeologists, artists, authors, architects, historians and others, and today is an icon of ancient astronomy.

Many of the astronomically significant monuments are now largely or wholly buried (e.g. Woodhenge). While their astronomical significance is not readily apparent on the ground, their remains are preserved underground and their authenticity is not affected.

Quote from ICOMOS on Stonehenge – with image in background – The new Management Plan for Stonehenge and Avebury recognises that Stonehenge’s astronomical associations form an important aspect of the monument’s overall significance, even though this was not part of the reason for its inscription. This leads to the recognition of the importance of maintaining as dark as possible a night sky, and of encouraging night tourism in relation to the site.’

STONEHENGE AND AVEBURY UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE

DISCOVER STRASBOURG GRANDE ILE

The most widely known of these astronomical displays are the cathedral’s elaborate astronomical clocks. These clocks have undergone successive transformations through the centuries. The 14th-century clock included a calendar, a mechanically driven stereographic projection showing the movement of the stars, and pointers showing the positions of the Sun and Moon. On top of the clock was an automaton of a cockerel, which crowed at noon, flapping its wings!

The 16th-century clock added a rotating celestial sphere on which were depicted all 1,020 stars of Ptolemy’s star catalogue, together with figures of 48 constellations, a disc showing the ecclesiastical calendar for 100 years, and depictions of all eclipses over an interval of 32 years.

LEFT, THE ASTRONOMICAL CLOCK

The original clock was built in 1571 by Conrad Dasyapodius & the Habrecht brothers and functioned until the 18th Century. Today’s existing clock originated in 1838-1843. Photo by Frank Müller.

A stereographic projection of the stars, Sun and Moon, like the one in the original clock, was enhanced with additional pointers showing the positions of all the visible planets and the ‘Dragon’, or lunar node, which served to explain eclipses. The 19th-century clock reflected Copernican astronomical concepts. The geocentric stereographic projection of the Sun, Moon, and planets was replaced by a heliocentric model of the visible planets, plus the Earth and Moon, in the solar system. It displayed both uniform civil time and the apparent time indicated by the daily motions of the Sun.

The stellar globe now portrayed more than 5,000 stars, extending down to faint sixth magnitude ones. In addition, the clock incorporated a perpetual calendar, computing the ‘solar’ cycle of 28 years, the lunar cycle of 19 years, the date of Easter, and other calendrical parameters traditionally found in ecclesiastical computus. The builder of the 19th-century clock, Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué, installed a vertical meridian line inside the entrance to the south transept marking local apparent noon to regulate the clock.

THE CLOCK’S DETAILS

The original 16th century clock can now be seen in the Strasbourg Museum of Decorative Arts. Photos by Jon Berghoff.

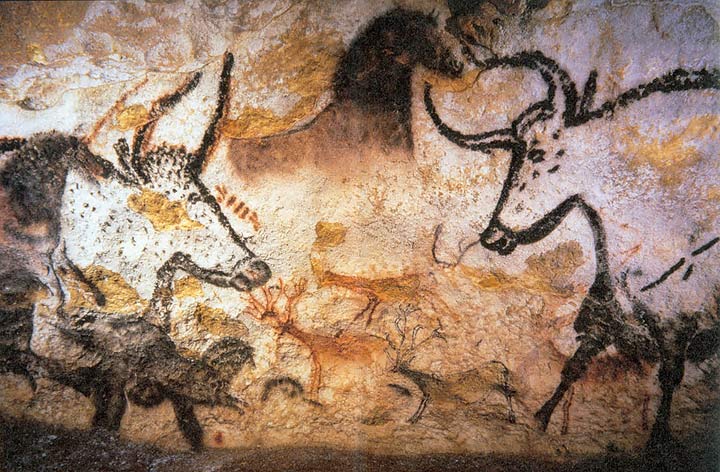

DISCOVER THE VEZERE VALLEY

The Vézère Valley’s significance stems from its cave paintings, especially those of the Lascaux Cave, whose discovery in 1940 was of great importance for the history of prehistoric art. The hunting scenes show some 100 animal figures, which are remarkable for their detail, rich colours and lifelike quality. In 2000, a prehistoric map of the night sky was discovered on the walls of the Lascaux Cave.

A number of the Lascaux pictures have possible astronomical significance. These include the ‘Chinese horse’ and ‘fronting ibex’ in the Axial Gallery and the ‘crossed bison’ in the Chamber of Felines, and five ‘swimming stags’ in the Nave. When viewed in this way, the Lascaux caves contain the most elaborate and complex astronomical notations in earlier prehistory so far recognised.

The majority of the animals depicted at Lascaux show seasonal characteristic features: the deer are represented in their rutting season at the start of autumn, the horses at their time of mating and foaling in late winter/early spring, the ibexes at the time when they congregate in same-sex herds during the late summer/early autumn, and so on. These indications of particular seasons are sometimes enhanced by the addition of stylized plants: an example is the ‘Chinese horse’ in the Axial Gallery that is shown in its summer fur, highly pregnant and surrounded by stylized branches, illustrating the time of foaling around summer solstice.

THE DANG DYNASTY STELE

DISCOVER DENGFENG

Two astronomical monuments remain in Dengfeng: an observatory of the Yuan Dynasty (originally built in 1279 by Guo Shoujing) and a stele of the Tang Dynasty. The main feature of the Yuan Dynasty Observatory is a device for measuring the length of the sun’s shadow at noon and tracing its variation through the year. It functioned by casting the shadow of a horizontal bar down onto a large horizontal scale extending to the north. This innovative design effectively created a gnomon five times the height of the standard gnomon used for the same purpose through Chinese history.

The centre of heaven and earth in astronomical terms is used as a propitious place for a capital of terrestrial power, and Mount Songshan as the natural symbol of the centre of heaven and earth is used as the focus for sacred rituals that reinforce that earthly power. The buildings that clustered around Dengfeng were of the highest architectural standards when built and many were commissioned by Emperors. They thus reinforced the influence of the Dengfeng area.

The Observatory is very clearly associated with the astronomical observations made at the centre of heaven and earth, while the remainder of the buildings were built in the area perceived to be the centre of heaven and earth, for the status that this conferred.

Astronomers considered Yangcheng the best place for astronomical observations, and especially for measuring the length of the sun’s shadow. Since the summer and winter solstices, and hence the length of the tropical year, were determined in this way, traditional Chinese calendars paid special attention to the sun’s shadow.

DISCOVER JANTAR MANTAR

They are monumental examples in masonry of known instruments but which in many cases have specific characteristics of their own. Designed for the observation of astronomical positions with the naked eye, they embody several architectural and instrumental innovations. This is the most significant, most comprehensive, and the best preserved of India’s historic observatories. It is an expression of the astronomical skills and cosmological concepts of the court of a scholarly prince at the end of the Mughal period.

The instruments are still in a usable state, and staff or authorized persons are able to perform astronomical observations. For science, the main goal is to maintain the instruments through use, by increasing their capacities for current users.

Jantar Mantar is the most complete and best-preserved great observatory site built in the Ptolemaic tradition. This tradition developed from Classical Antiquity through to Medieval times, and from the Islamic period through to Persia and China. Jantar Mantar was greatly influenced by earlier great observatories inside central Asia, Persia and China. The observatory was very active during the life of Jai Singh II, with around 20 permanent astronomers.

The main aims of Jai Singh II’s scientific programme were to refine the ancient Islamic zīj tables, to measure the exact hour at Jaipur continuously and to define the calendar precisely. Another aim was to apply the cosmological vision deriving from the Ptolemaic one, based upon astronomical facts, to astrological prediction—both social (e.g. predicting monsoon and crops) and individual (e.g. printing almanacs). This was an important period for the popular adoption into the ancient Hindu tradition of astronomical data coming from Islamic and Persian civilization. The interweaving of science, cosmology, religion and social control has had a great importance in Rajasthan culture since the 18th century, and continues into current times.

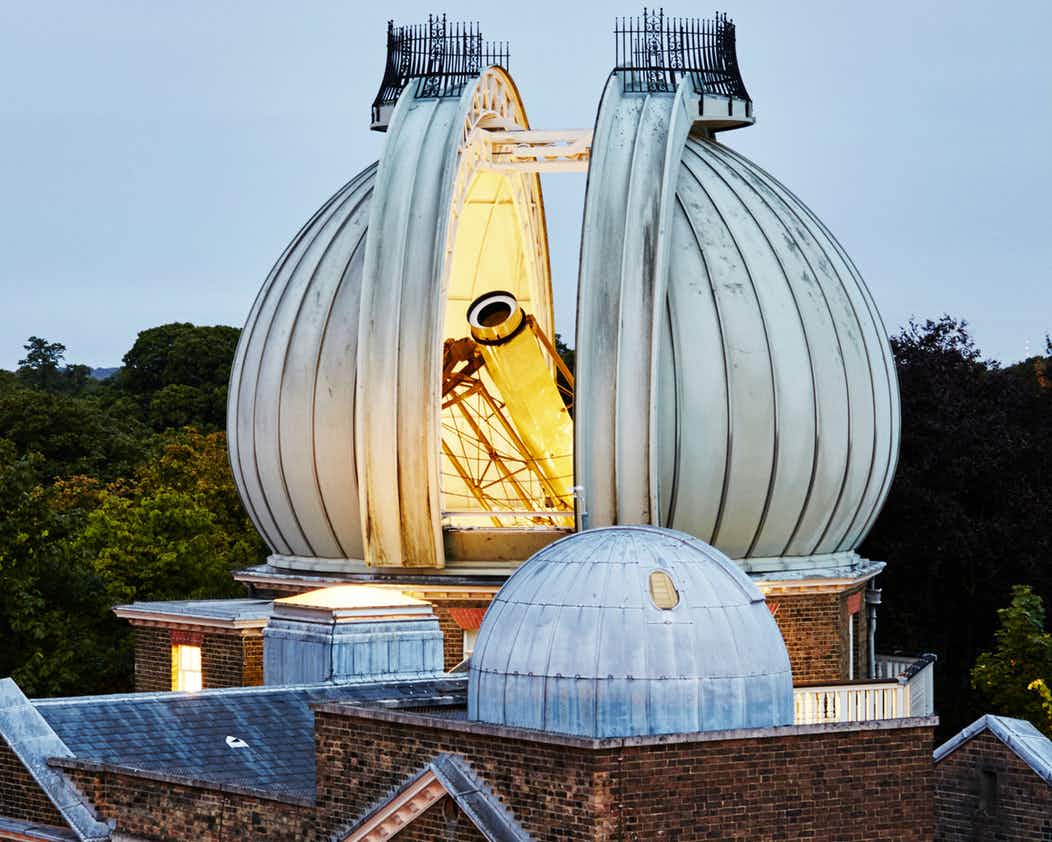

DISCOVER THE ROYAL OBSERVATORY, GREENWICH

The Royal Observatory’s astronomical work, particularly of the scientist Robert Hooke, and John Flamsteed, the First Astronomer Royal, allowed the accurate measurement of the earth’s movement and also contributed to the development of global mercantile navigation.

The Royal Observatory was founded by Charles II in 1675 to produce astronomical data that would aid navigation. Successive Astronomers Royal contributed to this project with a programme of meridian observation, leading to a successful solution with the publication of the Nautical Almanac from 1767. Work expanded in the 19th century to include magnetic and meteorological observation, photography, spectroscopy and timesignals.

The Royal Observatory is inextricably linked to concepts of time and Greenwich is now the base-line for the world’s time zone system and for the measurement of longitude around the globe.

ENGAGE WITH THIS SITE

Events at the Royal Observatory

The Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy has been developed in partnership with the World Heritage Centre.

It was developed with the aim to support UNESCO’s Thematic Initiative “Astronomy and World Heritage” and to raise awareness of the importance of astronomical heritage worldwide and to facilitate efforts to identify, protect and preserve such heritage for the benefit of humankind, both now and in the future.

Home → What’s On → News → Astronomy and UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Read more about Jodrell Bank, from our long reads to our short stories and portraits.

Home → What’s On → News → Astronomy and UNESCO World Heritage Sites